Housing study says 90,000 new units will be needed by 2040

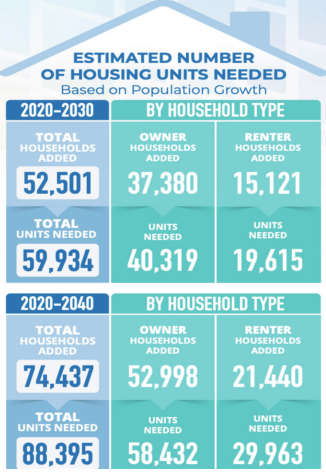

Over the next 17 years, New Hampshire will need to build 90,000 units of housing, according to an assessment study released this month.

That includes the state’s current housing shortage of more than 23,500 units needed today to stabilize the housing supply.

The state’s housing crisis comes as the median home price rose 50 percent from 2019 to 2022, making middle and higher-middle-class renters less likely to become homeowners.

With the state’s extremely low vacancy rate — 0.5 percent statewide — the rental market favors high-income tenants pushing rents out of range for others, especially lower-income renters. Compounding the problem are rent and home price increases outpacing wage growth.

Between 2000 and 2020, New Hampshire’s home sales prices rose 111 percent, and rents increased 94 percent, while household median incomes increased only 73 percent.

That is some of the data contained in the 2023 New Hampshire Statewide Housing Needs Assessment prepared by Root Policy Research for New Hampshire Housing.

The bottom line is New Hampshire just does not have enough housing to meet demand, which is why both the prices of houses and rents keep increasing.

The assessment found that between 2020 and 2030, 60,000 more units of housing are needed; another 90,000 are needed between 2030 and 2040. Those totals don’t account for seasonal residences and second homes; that’s another 13,800 to 23,300 units by 2040.

While household incomes rose by 25 percent between 2010 and 2020, that was partly due to wealthier people relocating to New Hampshire.

Those of working age are also increasingly likely to rent rather than own — a trend that is related to the rising costs of houses which, in turn, is caused partly by insufficient supply.

There are many challenges as well for those who rent, particularly if their income is low. With an overall vacancy rate of 0.5 percent, it means that if 10 percent of the state’s lower-income renters wanted to move — about 7,400 renters — there would be about 350 units available for them to choose without overpaying. These renters would have about a 5 percent chance of finding an affordable, vacant unit.

Apartments in New Hampshire generally rent for between $1,000 and $2,000 a month. At the same time, many lower-cost apartments are occupied by higher-income renters who “rent down” because higher-end rental units and homes to buy are in short supply. Landlords are more likely to rent to those with a higher income, further limiting the options for someone earning less.

Currently, there are 23,000 tenants in the state paying a higher rent than the amount affordable for their income level.

Drop in homeownership

The study also said a small proportion of the state’s rental housing stock has a contract with or is managed by an entity that ensures the apartment is affordable for someone with a low income. Among rental housing with U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development funding, the average tenant income is under $18,000.

According to the study, “Public resources have historically been inadequate to meet needs.” Housing Choice Vouchers, formerly known as Section 8, address the affordability gap. However, the study said vouchers are less effective in tight rental markets, when property owners can raise rents above subsidy levels, or simply choose not to rent to voucher holders. Unlike all of the other New England states, New Hampshire does not have a law prohibiting discrimination based on source of income.

Because homes in New Hampshire are so expensive, more people are staying put in apartments.

The statewide median price of a home sold in the first three quarters of 2022 was $430,000, up from $285,975 in 2019. In just three years, the median price rose by 50 percent.

At the same time, homeownership dropped among working-age adults, particularly those ages 25 to 44. Across income ranges, the biggest decline was households with incomes of $75,000 to $100,000, falling from 84 percent to 75 percent. The state’s homeownership rate overall decreased from 73 percent to 71 percent between 2010 and 2020.

Also, according to the study, middle- to higher-income households are less likely to become homeowners.

For renters with incomes of 61 to 100 percent of area median income looking to buy — about 3,700 renters — they would have about 550 units from which to choose without overpaying. “They would have about a 15 percent chance of finding an affordable home to purchase,” according to the assessment.

To stabilize the state’s housing market and restore it to functional vacancy rates — 5 percent for rental units and 2 percent for ownership units — 10,905 additional rental units and 12,764 ownership units are needed. In other words, the study says, “A total of 23,670 housing units are needed today. This is New Hampshire’s current housing shortage.”

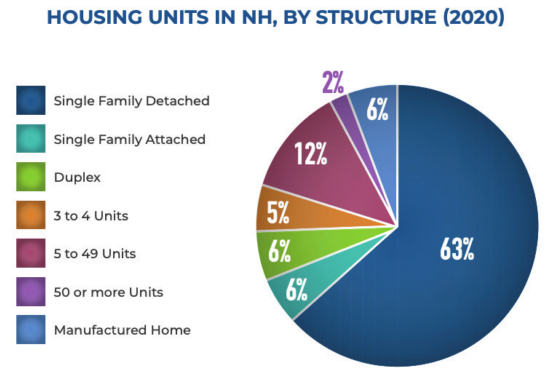

To accomplish the goal of 90,000 units, the state needs to increase building permits by 36 percent statewide. (From 2017 to 2021, about 4,000 building permits were issued per year.) “The only plausible way that this could be achieved is through a combination of local and state action,” the study says.

The study listed a number of ways the state can meet its housing needs:

• Incentivize higher-density development.

• Increase use of funding programs for preservation and health improvement to older housing stock in established town centers and neighborhoods.

• Support inclusionary zoning requirement in communities with stronger markets for new housing construction.

• Support expanded manufactured housing development and conversion of manufactured home parks to cooperative ownership to maintain their availability as an affordable housing option.

• Support local land-use allowances for smaller houses, particularly those with co-op ownership models, to provide more efficient use of land and infrastructure.

• Allow development of housing without special zoning permits such as duplexes, as well as increased allowances for “missing middle” housing types such as cottage courts, triplex/quadplexes and mixed-use development.

• Increase opportunity for detached accessory dwelling units, including the removal of permitting barriers.

• Encourage conversion of commercial and office real estate and properties to residential use through streamlined permitting and tax incentives.

This article is being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.