If left unfixed, state code could cost businesses over $90m

New Hampshire businesses could save a total of over $90 million in business profits tax payments — more than twice the amount that would be saved under a proposed BPT rate cut — if the state foregoes taxing forgiven Paycheck Protection Program loans, according to state Department of Revenue Administration estimates.

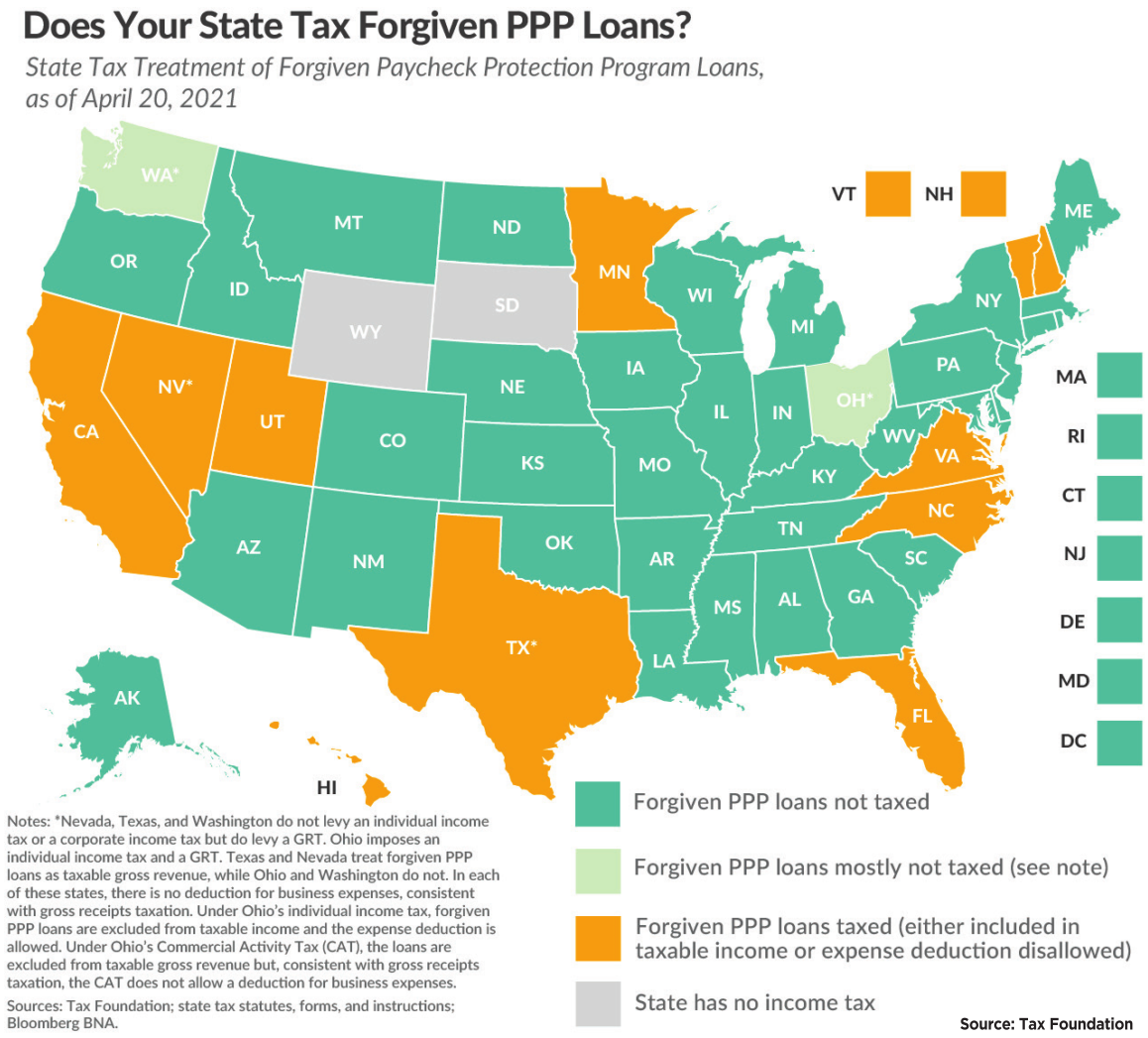

But thus far New Hampshire is one of 10 states that is taxing PPP loans — a testament to its outdated and unique tax codes. And that is why Senate Bill 3 — which would exempt PPP loans from being taxed — might very well surpass any other legislation, aside from the budget itself, when it comes to economic impact.

As of April 25, the PPP provided at least 25,000 New Hampshire businesses with $3.5 billion in forgivable loans, and counting.

The PPP “helped get us through our darkest hour,” said Larry Haynes, CEO of Grappone Automotive Group in Bow, which got $3.5 million last April.

The SBA-guaranteed loans are forgiven if the borrower can show it spent the proceeds on payroll and other specified expenses.

That

hasn’t happened yet for Grappone — the processes can be painfully slow.

But when it does, Haynes could be faced with a whopping tax bill.

“The spirit of this was to keep people employed,” he said.

It

was also the intention of Congress to not tax PPP as income — it’s in

the law. But the Internal Revenue Service first took that to mean that

it could render the expenses that it was used for as nondeductible to

prevent what it said would be double-dipping. But Congress thought that

the agency was thwarting its purpose, so in the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, passed in December, it made it clear that businesses

could discount income and deduct the expenses.

“The

best of both worlds,” summed up Kevin Kennedy, a certified public

accountant on the March 17 episode of NH Business Review’s “Down to

Business” podcast.

More

than half of the states went along with the law automatically. That’s

because they are “rolling conformity states,” and they go along with any

changes in tax law that the federal government makes. That makes it

easier for businesses and accountants, though sometimes it means

adopting changes that may not be business-friendly.

New

Hampshire, however, is what is known as a “static conformity state.” It

ties its tax code to a certain date, and then spends years figuring out

what it wants to include in the next update. This is partly because New

Hampshire lawmakers don’t like the idea of Washington telling them what

to do, and because our tax structure is so different from other states.

So, in 2021, New Hampshire’s tax code is tied to the IRS code of 2018. And in 2018, all forgivable loans were taxable.

The

DRA does allow expenses to be deducted, DRA commissioner Lindsey Stepp

told the House Ways and Means Committee on April 27. To do otherwise

would make it a benefit, a policy decision that would have to be spelled

out in state law.

‘Hanging by their fingernails’

Forty states are following the IRS’s lead, either through conformity or by adopting it, according to the Tax Foundation.

The

latest were Arizona, on April 14, and Massachusetts, which excluded PPP

under the state’s individual income tax (it already did so under its

corporate income taxes via rolling conformity) on April 1.

That leaves New Hampshire and Vermont as the only states in New England that are taxing PPP loans.

That doesn’t sit well with Senate Majority Leader Sen. Jeb Bradley, R-Wolfeboro, who introduced SB 3.

“If in Washington it isn’t a taxable event, we shouldn’t make it a taxable event,” he said.

He

noted that the PPP money only went to businesses with under 500

employees. “Quite frankly, it would hurt Main Street business. It would

hurt our competitiveness on a national scale,” said Bradley.

“There

are a lot of our members hanging on by their fingernails,” said Mike

Somers, President of the New Hampshire Lodging and Restaurant

Association, who said he would also like to expand the tax break to

grant programs, such as federal Emergency Injury and Disaster Loan

Advance, the Restaurant Revitalization Fund and the state’s Main Street

Relief Fund.

In

reality, the PPP tax wouldn’t apply to most small businesses since many

mainly pay the business enterprise tax, and others are too small to pay

any business tax.

Yes,

the BET taxes payroll and other expense covered by the PPP, but

exempting the PPP money from taxation won’t affect their tax bill.

But for those that do pay the BPT, it could hurt a lot.

For

Procon LLC, PPP is the only reason it paid the BPT last year. The $3.5

million PPP loan the Hooksett-based construction company received last

year put it in the black, said CEO Mark Stebbins. The company could have

eked out a profit anyway, he said, but he would have had to lay off a

lot of people.

“I

think the state should follow the government’s lead,” he said. “What’s

the sense of giving money out and then taking some of it back? Why

subsidize business and then tax them on the subsidy?” On April 5, Procon

got a second-round PPP loan of $2 million in what is promising to be a

more profitable year. The company has been hiring and is now up to 150

employees, but if he has to pay taxes on both loans, Stebbins said, “we

have to make a decision. We will have less opportunity to grow because

we have less cash to grow with.”

The

question is probably moot for Stebbins’ other major business. The

Portsmouth-based Schleicher & Stebbins, which has three hotels in

Portsmouth and one in Lebanon and employs 75 people (half of

pre-pandemic levels), didn’t come close to a profit last year.

“I can’t wait to be paying the business profits tax again,” Stebbins joked.

Stebbins said all the hotels, filing separately, received PPP funding, at least $1.6 million,

according to SBA records. Business is expected to pick up this summer,

but a looming tax bill might dampen hiring, Stebbins said.

Michael

Benton, owner of several fitness clubs, including the Executive Health

and Sports Center in Manchester, had 250 employees on the payroll during

the lockdown thanks to PPP loans totaling more than $1.2 million.

“One

hundred percent went to payroll,” he said, adding he shouldn’t have to

pay taxes on “money that was granted for me to stay alive.” Even as

business picks up, a third of his business is currently gone and he has

been reluctant to hire because of the tax bill and the slow pace of

forgiveness.

Estimating the impact

Forgiveness

is more of a concern than taxes for Grappone, said Haynes. The Concord

dealership applied for it in November, but his application, like so many

others, was put on hold for the second round of funding, which ends May

31.

“We don’t know what is going to happen. It’s a big cloud over our head,” Haynes said.

The

forgiveness aspect of the program complicates DRA estimates of the cost

of making PPP tax-free, because it is only when the loans are forgiven

that they become taxable. So even though the bulk of loans were made in

2020, by the end of the year, the SBA had forgiven less than a fifth of

them, and by April 25 half were still in limbo. The process to forgive

the second round hasn’t even begun yet. And there is no telling how many

loans will be taxable in what fiscal year.

So

even though the DRA knows that the state’s businesses have received

$3.5 billion in PPP loans so far, that doesn’t do it much good,

especially since the SBA data doesn’t easily match up with the state’s

data system.

Instead,

the agency started by looking at the national figure of $762 billion in

PPP money awarded in both rounds as of April 18 and adjusted it for New

Hampshire’s share under apportionment. It knocked off about 20% that was

awarded to nonprofits and came up with $2.4 billion in taxable business

PPP income in New Hampshire.

After

accounting for various thresholds and the BET, and assuming all would

be forgiven, the DRA calculated a revenue hit of $91.7 million for no

particular year.

The

$91.7 million estimate doesn’t account for $50 billion left in the

program to be parceled out by the end of May. That’s both better and

worse than an earlier calculation, which said the hit would be in the

ranges of $80 million to $135 million.

Either

way, it is a much greater amount than the DRA’s estimate impact of

proposed cuts in the BPT and BET rates — $53.7 million over four years

and $33 million over the next two. The DRA didn’t break out the specific

impact of the cut in the BPT, which currently accounts for 63% of the

state’s business tax revenue, so it is likely that revenue hit of not

taxing PPP loans (and the tax savings for businesses) would be at least

twice, if not three times, that of the BPT rate cut.

There

are major differences. The BPT cuts go on and on, and the PPP tax break

is a one-time deal. The BPT is paid by all businesses that make a

profit, but the PPP tax break would only help profitable businesses who

got the loans.

But

there may be an even greater difference, and that has to do with the

American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which forbids a state from using that

money to reduce taxes, including business taxes.

However,

on April 7, the Treasury Department released a statement that states

they are simply conforming to federal tax law — including the PPP

provision — and would not be engaging in a tax cut, therefore not

endangering any ARRA funding.

The

DRA is awaiting more detailed guidance than the three-paragraph

statement, but several Ways and Means Cmmittee members were hopeful the

PPP tax break could simply be replaced with ARRA funds.

“If

the state is able to use that new income, then there is no revenue

loss,” testified David Juvet, senior vice president of public policy at

the Business and Industry Association of New Hampshire, which supports

PPP tax exemption.

That

doesn’t mean the bill will face smooth sailing in the House. Although

SB 3 passed unanimously in the Senate, several committees questioned why

businesses should get a break on both the income and the expense side.

“Can

a business use it in two ways to get a double deduction?” asked Rep.

Walter Spilsbury, R-Charlestown, at the April 27 hearing. And Rep. Tom

Schamberg, D- Wilmot, said that the money could be better spent on

priorities like healthcare.

The

Ways and Means Committee said it planned to hold at least one work

session on the bill, indicating it might get more scrutiny. But no

matter what the House does, Bradley indicated that the Senate leadership

planned to put it in its version of the budget.

“We are not in the tax-raising business in New Hampshire,” he said.

Bob Sanders can be reached at bsanders@nhbr.com.

Most small businesses do not pay the Business Profits Tax, but for businesses that do, it could hurt a lot.