Enthusiasm among housing advocates is high for moving the needle forward to increase the residential supply throughout New Hampshire.

But, while enthusiasm and public support for changes in legislation, policy and zoning are high to make housing more available and more affordable, 2024 has been a mixed in terms of results.

Except for some movement for the approval and construction of accessory dwelling units (ADUs), little changed in 2024 to

increase the opportunities in towns and neighborhoods to build the kind

of affordable and workforce housing that New Hampshire needs to meet

future demand.

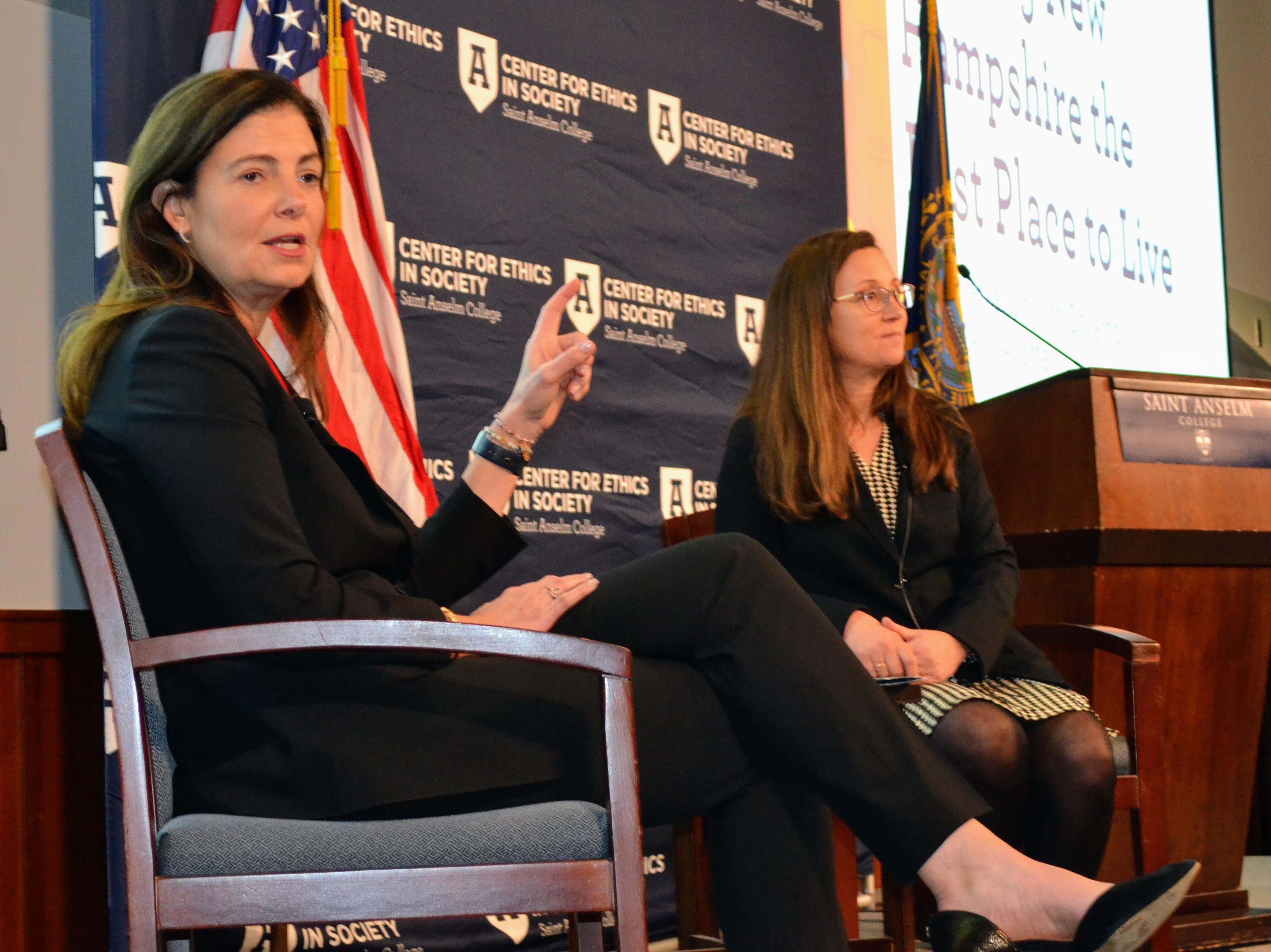

Governor-elect

Kelly Ayotte, left, makes a point during her remarks at the housing

roundtable forum held Dec. 13 by the Center for Ethics in Society at

Saint Anselm College in Manchester. At right is moderator Elissa

Margolin, recently named director of housing programs at the college. (Photo by Paul Briand)

“There

has been little to no change in the percentage of buildable area for

other housing types since the atlas release in 2022,” said Noah

Hodgetts, principal planner at the Office of Planning & Development

at the New Hampshire Department of Business and Economic Affairs.

“In most communities in New Hampshire, it’s still difficult to build anything but large-lot, single-family homes,” he added.

Those

are some of the talking points drawn from a day-long housing roundtable

forum held Dec. 13 at Saint Anselm College in Manchester by the

school’s Center for Ethics in Society.

The center pulled back the curtain on restrictive housing zoning

policies statewide when it revealed in May 2022 the Zoning Atlas that

offers a graphical, detailed look at how communities limit and

discourage housing development through their zoning.

This was the forum’s seventh year, attracting some 180 people to the event at the St. A’s New Hampshire Institute of Politics.

“I’d

like to think that over these seven years we’ve helped move the needle a

little bit on knowledge and information, on some of our attitudes and

perceptions in the state, certainly, hopefully, on legislation and

policy,” said Max Latona, executive director of the college’s newly

created Office of Partnerships.

As

the college’s former executive director of the Center for Ethics in

Society since its founding in 2017, he was the fronting face and vocal

force in the release of the Zoning Atlas.

Statistically,

the need for housing is clear and public support for housing is

overwhelming, according to data provided at the forum.

The New Hampshire Council on Housing Stability says the state needs 90,000 new housing units by 2040 to keep up with demand.

To illustrate public support, Latona pointed to surveys commissioned by the center and done by NH Institute of Politics.

A

survey of Granite Staters showed 75% support the notion that

communities need for more affordable housing. “Even more starkly, 59% of

people said, ‘My own neighborhood needs more affordable housing to be

built,’” said Latona.

A

separate survey among business leaders in the state showed that 86% of

them cited housing as their top challenge, even head of workforce

hiring, and 85% agree that lack of housing makes it a challenge for them

to attract and retain workers.

“These

are our business leaders, which are offering their vital economic

activity to the state, telling us that housing needs to be addressed,”

said Latona.

Some of the enthusiasm for 2025 held by housing advocates is rooted in

new political leadership in the state — Kelly Ayotte succeeding

Christopher Sununu as governor, Sharon Carson succeeding Jeb Bradley as

president of the state Senate.

“So

what are we looking at in 2025? There’s a lot of new industry

coalitions. Leaders are coming together. More organizations who have

either been on the outskirts of this fight or been starting to dip their

toes in the water are taking that next step in leveraging their

networks, bringing people together for this upcoming session,” said Nick

Taylor, executive director of Housing Action NH.

“There’s

that new governor, Governor Ayotte, coming in here with a robust

housing plan, and really made that a central part of her campaign,

saying that we need to move forward on this issue, one of the most

pressing issues facing our state,” Taylor added. “At the State House,

there’s a new senate president, there’s that growing bipartisan housing

caucus, and there are other committees and subcommittees being formed

to continue to make that legislative process more fruitful.”

For

her part, Ayotte used the analogy of “levers” that have to be pulled

this way and that to effect enough change to produce the projected

housing that’s needed in the decades ahead.

She

talked about one lever involving permitting that developments often

need from an alphabet soup of state agencies. Often a development can

get stuck in approval from one agency, and she wants to overhaul the

process to offer more congruence and transparency.

In

terms of what she called a “bigger lever,” she pointed to the NH

Housing and Finance Affordable Housing Fund. “That’s an important one,”

she said.

“Thinking

about you guys, I know you worked hard on the ADU legislation in the

last legislative session., I hope that issue is taken back up again,”

Ayotte added. “That issue lets families stay together too, right? So it

kind of makes sense, and though it’s a small lever, it can be an

important lever to keeping some families together.”

Another

lever she spoke of involved her and the state’s relationship with the

federal government, particularly grants from the U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

“If

we’re given some of those federal high dollars, we’ll maximize them.

We’ll get everyone to the table. We’ll make sure that they’re spent

sensibly and that we’re actually addressing the problem that whatever

the grant program has put to it,” said Ayotte.

The

governor-elect said she doesn’t intend on renewing a starter home

program in the state that provided $10,000 in a first-home loan

assistance.

“I think

that we’re only going to make this more affordable if we have more

housing,” said Ayotte. “That’s how markets work, and so I think that’s

where the priority has to be.”

Maggie

Goodlander, who will succeed Annie Kuster as the U.S. representative

from New Hampshire’s District 2, described politics as a “team sport.”

“And

it’s so true in the area of housing,” said Goodlander, “and that’s why,

after the election, one of the very first things I had a chance to talk

with Governor-elect Ayotte about was housing and how we can work

together.”

In terms of

housing-related legislation, Jack Ruderman, public affairs manager at

NH Housing, described the 2024 legislative session as a “turning point.”

“Lawmakers

on both sides of the aisle sought to eliminate barriers to expanding

the supply of housing and making housing more affordable. The outcome

was mixed. Some bills that were ambitious and far reaching didn’t make

it across the finish line, but a number of other bills addressing

various obstacles to building more housing garnered bipartisan support

and were enacted into law, taking the state in a new direction on

housing. Together, these bills provide a solid foundation to build on in

the coming legislative session,” he said.

ADUs will, again, be among the issues the Legislature will consider.

Current

law allows attached ADUs by right, in that they are allowed in all

districts that permit single-family dwellings, without discretionary

approval by a zoning board.

Detached ADUs, however, are allowed or denied at the discretion of zoning authorities.

With

the attention on zoning generated by the Zoning Atlas, some communities

have taken a deep dive into rezoning considerations. In some cases,

communities have eased up restrictions to allow more diverse housing.

Plymouth, cited as an example, has eased parking requirements for ADUs

and multifamily dwellings, reduced minimum lot sizes, and now allows

multiple single-family or two-family dwellings on a single lot in many

districts.

Other

communities have tightened their zoning restrictions, according to Jason

Sorens, senior researcher for the American Institute for Economic

Research. For example, Ashland, Barrington, Bradford, Durham, Epping and

Newport have specifically banned detached ADUs in certain districts.

“It

goes both ways,” said Sorens. Looking ahead to 2025, the Zoning Atlas

is expected to get another layer of data that includes public sewer and

water systems, where they are and where they aren’t. Lack of access to

sewer and water is often a barrier to housing development.