Researchers at the University of New Hampshire have been awarded $24 million to help build sensors that can track space weather and warn of dangers.

The sensors will monitor solar wind — a stream of charged particles flowing out of the sun that can interfere with the electric grid, satellites and flight paths.

Toni Galvin, a research professor working on the project, says solar wind is continuous, but its composition changes all the time. Sometimes it’s fast and sometimes it is slow, and under certain conditions, when it hits the earth’s magnetic field, it can cause problems.

“When a solar wind with a certain structure to it, like a coronal mass ejection or some such hits the Earth’s magnetosphere, then it can cause, let’s just say, a ‘jangling’ of that magnetic field around the Earth,” Galvin said.

Those coronal mass ejections, bubbles of plasma and magnetic fields ejected from the sun, are what allow us to see the aurora borealis, or northern lights. But they’re also one of the biggest causes of magnetic storms around Earth, which can disrupt a lot of things for humans.

NOAA

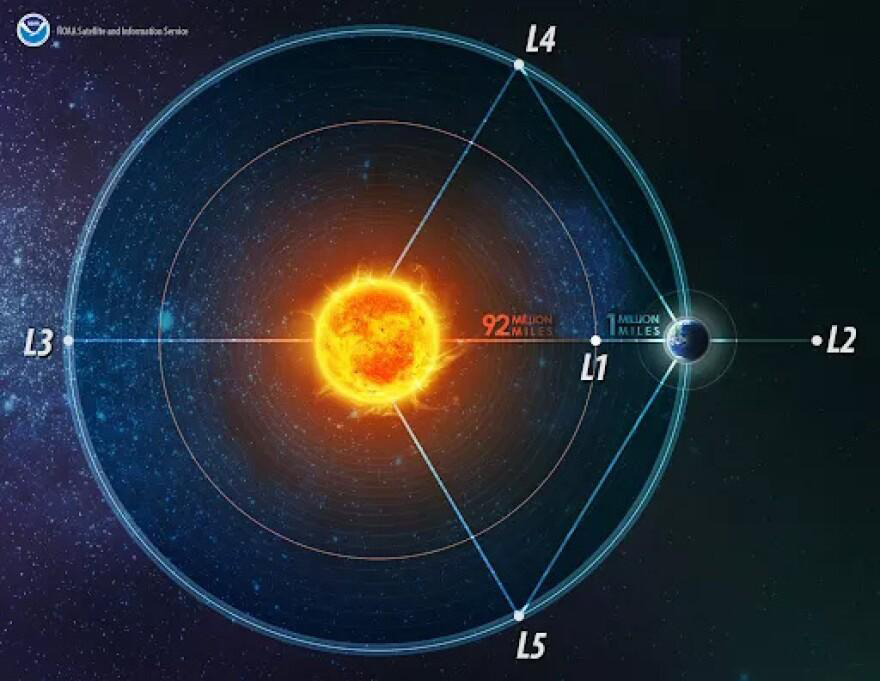

Lagrange Points of the Earth-Sun system (not drawn to scale). The

sensors UNH is developing will be located at Lagrange Point 1, about 1%

of the distance between the Earth and Sun.

“You know, if we were still cavemen, then we wouldn’t worry about it,” Galvin said. “But nowadays we have power grids. We have satellites.”

Those

storms can affect a wide range of systems, on Earth and in space: where

airplanes can fly, how GPS works, and the safety of astronauts on the

International Space Station. New England’s power grid operator says it

has procedures in place to address geomagnetic disturbances.

The

sensors the UNH team is building are meant to help raise the alarm if

solar wind could be dangerous. UNH researchers will work with NASA, the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Johns Hopkins

Applied Physics Laboratory to build two sensors over the course of nine

years.

They’ll be

located about 1% of the distance from the Earth to the sun. And they’ll

be able to give warnings of danger within 100 minutes for slow-moving

events and within 10 minutes for faster events.

“Everything has to be done very fast, very quickly, but also very accurately,” Galvin said.

— MARA HOPLAMAZION/NHPR