Alene Candles produces specialty lines at its Milford Factory

Matthew Link, production supervisor for the second shift at Alene Candles, talks about the Milford company’s new wicks assembly line. (Allegra Boverman) If you bought a candle from a name-brand retailer during the Christmas season, there’s a good chance it was made by Alene Candles, a Milford private-label company that produces more than 100 million candles every year.

Alene, founded in 1995 by Paul and Nancy Amato, was acquired by business partners Rod Harl and Ted Goldberg and a group of investors in 2008. The company opened a second factory in New Albany, Ohio, in 2012 and expanded that facility in 2020. It employs 1,100 people, including 450 in New Hampshire.

Alene has greater capacity at its Ohio factory than it does in New Hampshire, where the cost of labor, energy and housing are high, said Harl, Alene’s president and CEO. The New Hampshire location is also more constrained by geography; it’s expensive to ship materials in and out.

“We can’t do really, truly high-volume manufacturing here in the Northeast. So we do boutique work, and it means we can apply more skill to the product,” he said. “We do our high-volume work in Ohio, and we do our specialty work here.”

In October, Harl led a group from NH Business Review on a tour of the Milford factory, where we learned about the complexities of candle manufacturing, which relies on chemistry, engineering, ingenuity and hard work.

While automation has made candle-making more efficient, workers are needed along the production line to make adjustments, such as making sure wicks are straight after hot wax is poured into glass containers.

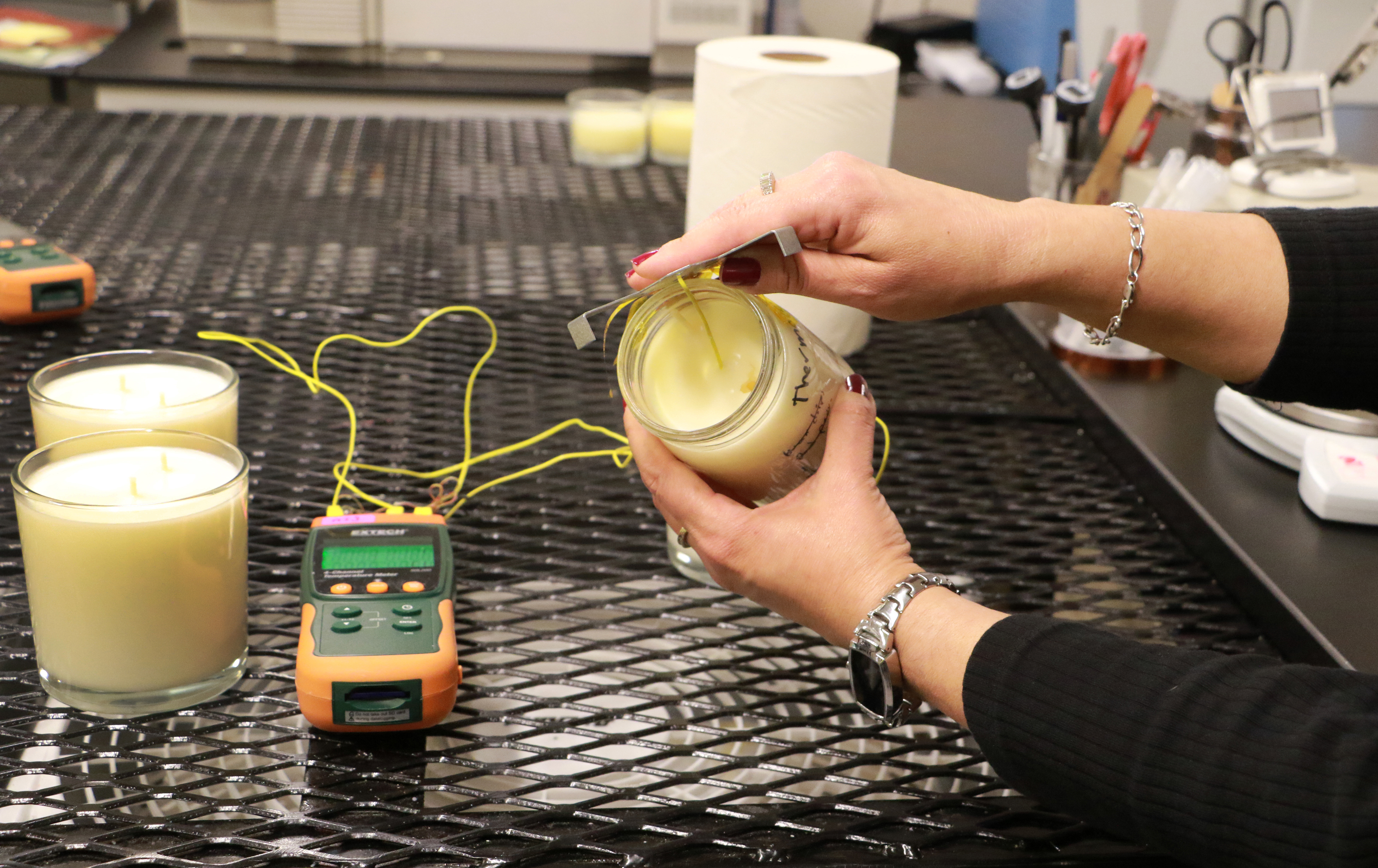

We started our tour at Alene’s research and development building, where work on new products begins.

While the company specializes in candles, it also produces a line of diffusers, which emit essential oils into the air to aid relaxation.

Alene makes candles housed in glass, pressed glass, metals, ceramics and lead glass, and the candles can weigh anywhere from a couple of ounces to nearly 3 pounds, said Lilia Morales Pruneda, director of research and development and analytical technical services.

“We’re always looking for new products that are available in the market,” Pruneda said. “Most of our waxes are either food grade, pharma grade or cosmetic grade, so you can pretty much fry doughnuts in the waxes that we use.”

Lilia Morales Pruneda, research and development and analytical technical services director at Alene Candles in Milford, discusses the various kinds of testing her labs do on candle wax burning, melting, cooling and more. (Photo by Allegra Boverman)

Lilia Morales Pruneda discusses the materials testing for containers for the candles Alene makes. (Photo by Allegra Boverman)

Once a new formula is tested, Alene offers it to its customers. Then the sample lab takes over.

“We take the customer’s preferred fragrance, and at the load that they want and the wax that they want, and then we will put it into the glass that they’ve chosen, whether it’s 3-pounder or down to the 2-ounce votives,” said Glenn Perrone, who manages the lab.

All the samples are made by hand. “I’ve got four technicians on two shifts who will then mix the waxes, mix in the fragrance, and if we have to do colors, they’ll mix the colors and make the colors as well,” he said.

Then the technicians will take the temperature of the candles.

“As they’re cooling, we’ll develop a cooling curve. We’ll pick the wicks and find a wick that works the best for the customer, with the safest flame, because we don’t want any candles burning up anyone’s houses.”

Before the sample candles are presented to the customer, they are tested in Alene’s safety lab.

“There’s a lot of testing going on to make sure that the wicks we choose will not overheat or cause any fracture of the glass or cause anything to burn or go out too soon,” Perrone said.

The company’s engineering team will feed that information into the production line, so workers know how fast to pour the wax, how hot it has to be and how fast to cool it, he said.

“Does it need a second pour? Does it need a second reheat to make the surface nice and smooth?” How the candle is going to be packed — which might include heavy Styrofoam packaging with a lid — is the final part of the development process, Pruneda said.

“To completely cool the candle, it could take up to 36 hours. So we need to consider that when we are manufacturing,” she said. “When are we going to be packing it? How are we going to pack it?” In another lab, chemists like Ibrahim Muhic run tests on the fragrances used in the various lines of candles, which feature 3,000 varieties, including 800 new formulations.

“We’re responsible for validating all new fragrance arrivals and making sure that they’re good to use before they move on to the sample and to be used in candles,” Muhic said. “When we receive a new fragrance, we’ll start off by looking at the documentation, the safety data sheets. We’re looking at component composition, physical chemical properties such as flashpoint, any other hazards that we should be aware of.”

Rod Harl, president/CEO of Alene Candles, discusses the various essential oils the Milford company receives to use in its candles. (Photo by Allegra Boverman)

Candles that are finished and inspected and ready to go are packed up for shipping at Alene Candles in Milford. (Photo by Allegra Boverman)

Work spaces are smaller and the volume is lower at these stages of the candle manufacturing process than they are on the factory floor. It’s where technicians are making sure ingredients are working as intended before the candles are approved for mass production.

On the production line, Matthew Link, a supervisor for the second shift, monitored a machine that was pouring hot wax into glass jars and sending them down a conveyor belt to waiting workers, ready to inspect them as they made their way toward a packaging station.

While the system is automated, workers make adjustments as needed.

“One of the things that’s big is making sure we hit the right temperatures. So they’re doing their temperature checks all throughout the day,” Link said. “It’s very important that you don’t have a cold wax going into a hot wax.”

The mix of automation and human hands improved efficiency along the production line.

“I can’t say it was a no-brainer. The technology existed, but we did make some improvement to it,” Harl said.

It’s the kind of investment the company is consistently considering as the industry evolves.

“The consumer will only pay so much for a candle, and you start to price yourself out of the market in terms of what’s sensible,” Harl said.