Dewatering and excavation activities being conducted in a contaminated sediment area at the Plaistow Beede Waste Oil Superfund site, where mismanagement and spills led to widespread PCB contamination. (NH Department of Environmental Services)

Liquid simmers and gurgles in the bulbous flasks sitting atop a multi-unit heating system. Drenched in fluorescent light, the complex chemistry contraption is continuously bathing clumps of soil, window caulking, concrete, paint chips and sediment in a solvent — a steady drip to strip the samples of an insidious contaminant.

Bubbling at the bottom of this particular lab-testing apparatus are polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs.

These toxic human-made chemicals seized the headlines in the late 1990s and early 2000s as a truer picture of omnipresent contamination began to emerge. Approximately 1.5 billion pounds were used across the U.S. in industrial products between the 1920s and 1970s.

Inside a Portsmouth office park, laboratory technicians at Absolute Resource Associates, an environmental testing firm, are analyzing countless contaminants: lead, arsenic, benzene, dioxin, mercury, MtBE and PFAS.

Each one has been the “toxin of the moment” at one point or another. But awareness comes and goes, as these concerns often seem amorphous. There’s always something new and emerging competing for the public’s attention; a threat on the horizon that seems more immediate.

The manufacture of PCBs was banned in 1979 because of health issues associated with exposure, but the hazardous contaminants are continuously found in air, water, soil and sediment today. They’re wholly unnatural, and yet became part of New Hampshire’s natural landscape. In turn, they’ve seeped into the anatomy of those who reside here, whether fish, loons or humans.

Experts say everyone in the world is likely to have quantities of PCBs in their body. Whether the toxins lead to health issues — like skin conditions and adverse effects on the immune, reproductive, neurological and endocrine systems — is dependent on the amount and length of exposure.

In animals, PCBs have been shown to wreak havoc and cause multiple kinds of cancer.

Last year, the state received millions of dollars from a settlement with the agrochemical giant Monsanto Company. Like many other states, New Hampshire had sued Monsanto — best known for its herbicide product Roundup — because it commercially manufactured nearly all PCBs used in the U.S.

The state’s lawsuit said PCBs have impaired 104 water bodies in New Hampshire, at least 63,000 acres of surface water, and at least 2.3 linear miles of the Souhegan River. Contaminated loon eggs have been identified in more than 20 lakes, the highest levels of PCBs being at Squam Lake.

But the $20 million settlement award didn’t go toward PCB-remediation efforts. Instead, it went into the state’s all-purpose general fund.

Funding to address PCBs is hard to come by, experts say, because federal resources are typically earmarked for Superfund sites with long-term cleanup and recovery plans in place.

New Hampshire has no active monitoring system at all for PCBs, said Jonathan Petali, a toxicologist at the Environmental Health Program within the Department of Environmental Services. He described PCBs as “up there with the rest of them” in terms of causing harm.

“We do a lot of upfront testing and say, ‘This is a problem,’ but interest in long-term monitoring usually drops off,” Petali said. “The public runs into fatigue … but these are not acute risks. With contaminants, it’s always been an issue, (the idea that) somewhere down the road something bad could happen. … Now attention, resources and concerns are shifting to these other priorities.”

What are PCBs?

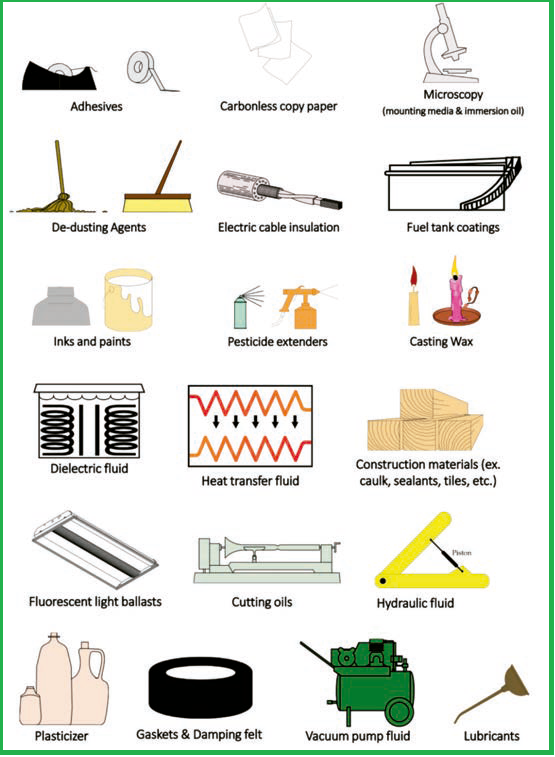

A class of more than 200 chemicals, PCBs were used in hundreds of industrial and commercial applications over six decades, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Because they don’t readily break down, the chemicals were seen as advantageous for use in electrical equipment, hydraulic fluids, heat transfer fluids, lubricants and plasticizers in paints and plastics.

Depending on the composition, PCBs can linger for decades or centuries.

If someone spilled a PCB-laden product in their backyard in the 1960s or ’70s, the chemicals are “probably still hanging out today,” Petali said.

And sometimes the spilling was on purpose. Dirt roads in New Hampshire used to be sprayed with oil containing PCBs to keep dust down. Rain then carried the chemicals into lakes, streams and creeks — where they remain.

Though manufacturing ceased, PCBs can be present in products made before the 1979 ban, and can still be actively released into the environment via poorly maintained hazardous waste sites, illegal or improper dumping, and leaks from older electrical transformers.

“I would put it up in a priority pollutant category even though it was banned in manufacturing in the ’70s,” said Andrew Hoffman, supervisor of Superfund sites with the Department of Environmental Services’ Hazardous Waste Remediation Bureau. “The reality is it’s a persistent pollutant. It doesn’t break down readily, so it stays in the environment. It is bioaccumulative; it does move up the food chain.

It is a very widespread pollutant.”

Hoffman said “we don’t really have a handle at all” on harm caused by PCBs in New Hampshire’s surface and inland waters in particular.

The most likely sources of PCB exposure for humans are the air they breathe, especially in old buildings with sealant or paint from before 1979, and the food they eat, such as contaminated fish or crops grown in PCB-polluted soil.

Vermont launched a first-in-the-nation push last year to test school air for PCBs after Burlington High School closed in 2020, when air testing found concentrations that significantly exceeded health and safety standards. Vermont lawmakers earmarked an unprecedented $32 million for the statewide endeavor.

Petali said PCBs are seen throughout the food web, can be carried long distances and build up over time. When a person eats a contaminated fish, especially a larger, older one, they’re inheriting the chemicals that fish accumulated over its lifetime.

That’s why the state has issued fish advisories over the years, telling people not to fish for consumption in certain waters.

Birth defects, developmental delays, liver damage and hormone interference have all been connected to high PCB exposure. Historically, workers who were exposed on the job suffered from skin conditions like chloracne and rashes. The EPA has deemed PCBs probable human carcinogens.

“It seems that it runs haywire on a lot of different systems in the body,” Petali said.

Aaron DeWees, chief operating officer at Absolute Resource Associates, said PCBs are one of the most common environmental contaminants they’re asked to test for at their Portsmouth laboratory. Once they provide statistical results back to clients, “people are making decisions that could be millions of dollars of excavating” or whatever remediation efforts are deemed necessary.

“It’s not something that goes away,” DeWees said.

“Once they’re in the environment, there’s very little that breaks them down. We see a lot of soil contamination, seeping down through the layers.”

Monsanto settlement

In 2022, New Hampshire received $25 million as part of a settlement with Monsanto, after the state sued the company in 2020. The complaint included copies of historical internal documents showing Monsanto allegedly knew about the potential for harm caused by their chemicals but continued to market and sell them to the public.

Bayer, the German pharmaceutical and chemical company that bought Monsanto in 2018, did not admit to any allegations brought forth by the lawsuit.

In celebrating the settlement award, Gov. Chris Sununu said it would ensure the state has “the financial resources necessary to remedy the harm that PCBs have caused to our environment.”

The lawsuit itself stated that New Hampshire will be forced to incur costs to combat the contamination, “costs which rightfully should be borne by Monsanto.”

But the $20 million left after attorneys’ fees and costs didn’t go toward PCB remediation at all, and was absorbed by the state’s general fund.

Michael Garrity, spokesperson for the attorney general’s office, said the state Legislature must pass a law in order to dictate where certain settlement funds go, as it has in the past with money from opioid, MtBE and Volkswagen settlements.

“There was no such law in place for these funds,” he said of the Monsanto settlement.

Ben Vihstadt, spokesman for Sununu, added that every settlement the state Department of Justice receives is placed into the General Fund unless the Legislature specifically redirects money elsewhere.

A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency chart shows some of the products PCBs were historically used in.

That’s why Sununu proposed using $6 million to establish a PCB Assistance Fund during this year’s state biennial budget process. House lawmakers took an ax to it when sifting through priorities this spring, cutting it back to $1 million.

A division of the House Finance Committee decided $1 million would give the Department of Environmental Services something to start with. A standalone bill could be introduced for further vetting next legislative session to provide additional funding, they said.

Comments by House members were representative of the challenge described by experts to communicate ongoing PCB risk. One lawmaker floated the idea of reallocating the funds toward PFAS instead, while another used the phrase “not super urgent” when discussing PCBs.

“The governor is hopeful that the fund remains at $6 million, and budget negotiations are ongoing,” Vihstadt said.

Beede Waste Oil Superfund site

In a wooded residential area of Plaistow, 40 acres of land off Kelley Road was, for decades, used as a waste oil recycling and disposal destination for thousands of residents and businesses across New England. Flowing along edges of the site is Kelly Brook, a tributary of the Little River.

Today, the property is surrounded by a chain link fence with no trespassing signs, a rather unsightly neighbor for those who live nearby. But most unsightly was what resided underground.

Starting in the 1920s, the Beede Waste Oil site housed operations such as waste oil processing and resale, fuel oil sale, contaminated soil processing into cold-mix asphalt, and antifreeze recycling, according to the EPA.

Hoffman, from DES, said extensive mismanagement, spills and leakage occurred on the property over the years, resulting in widespread PCB contamination. The state ordered the site’s closure in 1994. Oily liquid waste and sludge had seeped into the ground from a variety of sources, including a one-acre unlined lagoon and both underground and aboveground storage tanks.

Beede Waste Oil was declared a Superfund site in 1996, and in 2004, a $48 million cleanup plan was announced. A few years later, 12 companies that were once customers of the Beede Waste Oil Company formed a group and agreed to clean up the site under direction of the EPA.

As part of the site remediation process, 170,000 gallons of oil was removed from the ground in just one phase of the project.

New Hampshire has 22 active or pending Superfund sites, and those properties have some of the highest concentrations of PCBs. Superfund designation enables the EPA to work with states to clean up properties contaminated with hazardous waste, and it also forces responsible parties to either perform cleanups or reimburse the federal government.

But sites are often identified long after contaminants have run amok and made their home in the surrounding environment. In Plaistow, public water had to be provided to about two dozen neighboring properties whose private wells were contaminated.

Hoffman said Superfund sites are adequately funded by both federal and state dollars in terms of testing, cleanup and remediation efforts, but beyond them, there’s little known about the presence of PCBs in the broader New Hampshire environment.

“Moving outside of that, that’s where the contaminant source is undefined,” he said.

Loons and PCBs at Squam Lake

Tiffany Grade calls Squam Lake “a postcard picture,” with a well-protected shoreline and minimal industry. The beloved

summertime destination is much quieter compared to its freshwater body neighbor Lake Winnipesaukee.

A 1981 Academy Award-winning film starring Henry Fonda, Jane Fonda and Katherine Hepburn was filmed there called “On Golden Pond.”

“This was not the lake we thought this would happen on,” Grade said. “But that’s just it. These contaminants are so insidious. They’ve been banned for decades and yet here they still are.”

Grade is a biologist with the Loon Preservation Committee, a nonprofit formed in 1975 that has been privately funding loon egg testing across New Hampshire.

Between 2005 and 2007, Squam Lake’s adult loon population experienced an “unprecedented decline,” Grade said. About 44 percent of paired adults died in a single year due to a variety of compounding factors.

“This was something we had never seen before,” she said. “And this was followed by years of almost total reproductive failure.”

Egg and sediment testing funded by the Loon Preservation Committee and Squam Lakes Association led to an eye-opening discovery of elevated PCB levels. LPC went into its “egg archives” and tested eggs from the 1990s, which affirmed high PCB levels on Squam Lake stretched back decades.

“Back in the ’60s and ’70s, we know the dirt roads around here were sprayed with oil to keep the dust down,” Grade said. “And people would put PCBs into that oil. The site where we found elevated sediments, it’s immediately downstream of a dirt road. The working hypothesis is the road is the source.”

DES decided to piggyback off the research, which ultimately led to a fishing advisory in 2020 for smallmouth bass and yellow perch. The advisory said the state had concluded that PCB concentrations in Squam Lake fish “are high enough to present risks from exposure, and their consumption should be limited.”

Because of the Squam surprise, LPC decided to pursue a statewide probe of other water bodies.

Remediation activities at the Beede Waste Oil site in Plaistow have been ongoing for the last several years. (Courtesy of NH DES)

In 2021, the organization tested 81 common loon eggs from 24 lakes. Present in every single egg were PCBs, PFAS, organochlorine pesticides (including DDT and chlordane) and a class of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Up to 60 percent of the eggs exceeded chemical levels believed to cause negative health or reproductive effects.

Lakes with notably elevated levels of PCBs included Lake Francis, Merrymeeting Lake and Squam Lake.

Loons are high on the aquatic food web, Grade said, meaning “everything that affects the loon affects everything else that lives in and uses the lake.” Testing their eggs provides an important snapshot of a larger picture, one in which fish, loons and humans are intimately connected.

Grade believes LPC is the only entity actively doing this type of PCB monitoring in New Hampshire. She said the testing is “extremely expensive.”

LPC wrote in its 2021 report that it recognizes state agency funding is limited, and the testing itself is complex and pricey. “However,” the organization wrote, “we believe long-term systematic testing of high trophic-level lake wildlife is needed to address this issue and gain a better understanding of the extent, levels and potential impact of contaminants in New Hampshire’s lakes.”

Earlier this year, LPC and DES partnered to test 145 loon eggs for PFAS and a subset of other contaminants, including PCBs.

Interviewed for this story before the House of Representatives reduced the proposed $6 million for a PCB Assistance Fund, Grade said she was hopeful the money would help address what is “clearly a problem.”

“This is an issue that we feel really needs to be looked into,” she said. “One, Squam itself and what can be done there, the best course of action to deal with these contaminants. But also more broadly and statewide. Are there other places? And are there places where the state should be doing fish testing to look into human health risks?”

This story was originally produced by the New Hampshire Bulletin, an independent local newsroom that allows NH Business Review and other outlets to republish its reporting.