Project offers a graphical look at community limitations on development

Against the crushing need for new housing in New Hampshire, a comprehensive zoning map of the entire state is being introduced with the warning that continued exclusionary zoning practices blunt statewide economic growth.

“Local zoning barriers do impede economic growth statewide,” said Ben Frost, deputy executive director and chief legal officer at the New Hampshire Housing Finance Agency. “This is why the Business & Industry Association has taken up workforce housing as one of its top legislative priorities for many years, because without affordable places to live, your employees and employers will look elsewhere.”

Frost was one of the presenters at a May 8 media briefing prior to public introduction of the state’s first-ever zoning atlas.

The atlas will provide a digital, deeply detailed graphical display of all New Hampshire housing districts, town by town, zone by zone. In all, 269 jurisdictions are detailed, encompassing 2,139 districts, 23,000 pages of zoning regulations, and 400,000 pieces of data.

It is meant, according to its sponsors, to put the state’s zoning in context, to offer a graphical view of why the lack of affordable workforce housing has become such an important issue in the Granite State.

Zoning has moved away from its original intent to separate housing from industrial uses, according to Frost.

“In New Hampshire and elsewhere, in response to the building booms of the 1970s and the 1980s, municipal governments throughout the state used their zoning power significantly to limit or outright prohibit any growth except for large-lot, single-family development,” he said.

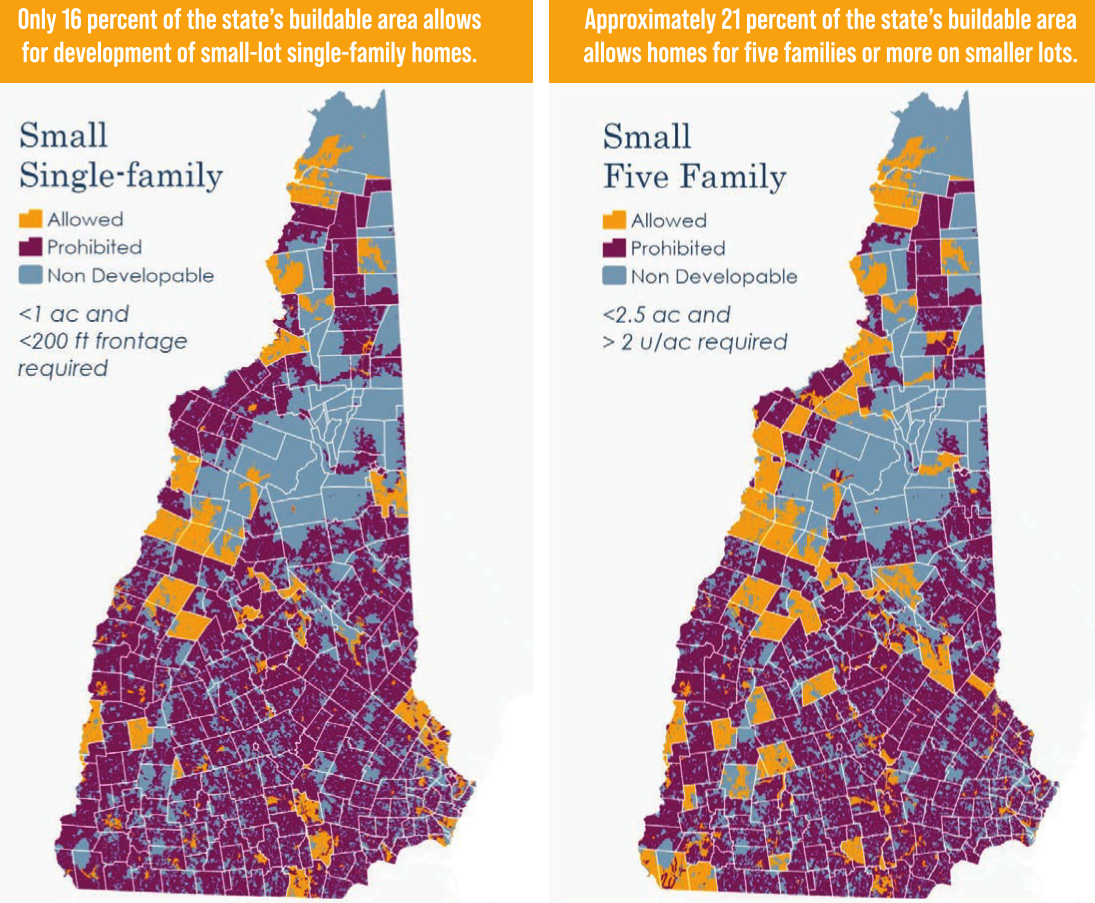

The atlas shows just how difficult it is to find available land zoned for single-family homes on small lots of less than an acre with less than 200 feet of frontage. Only 16 percent of the buildable land area in the state is available for small-lot, singlefamily development.

Even less area is zoned for small-lot, two-family homes. Only 11 percent of the state’s buildable area allows for this type of development. In fact, there is less twofamily zoning than there is for any other type of housing; 70 jurisdictions in the state don’t allow two-family anywhere.

Ironically, according to the atlas, it is easier to find zoning for multifamily dwellings of five units or more. Approximately 21 percent of the state’s buildable area allows for 5+ family homes on smaller lots, with an additional 1 percent for affordable or elderly restricted housing.

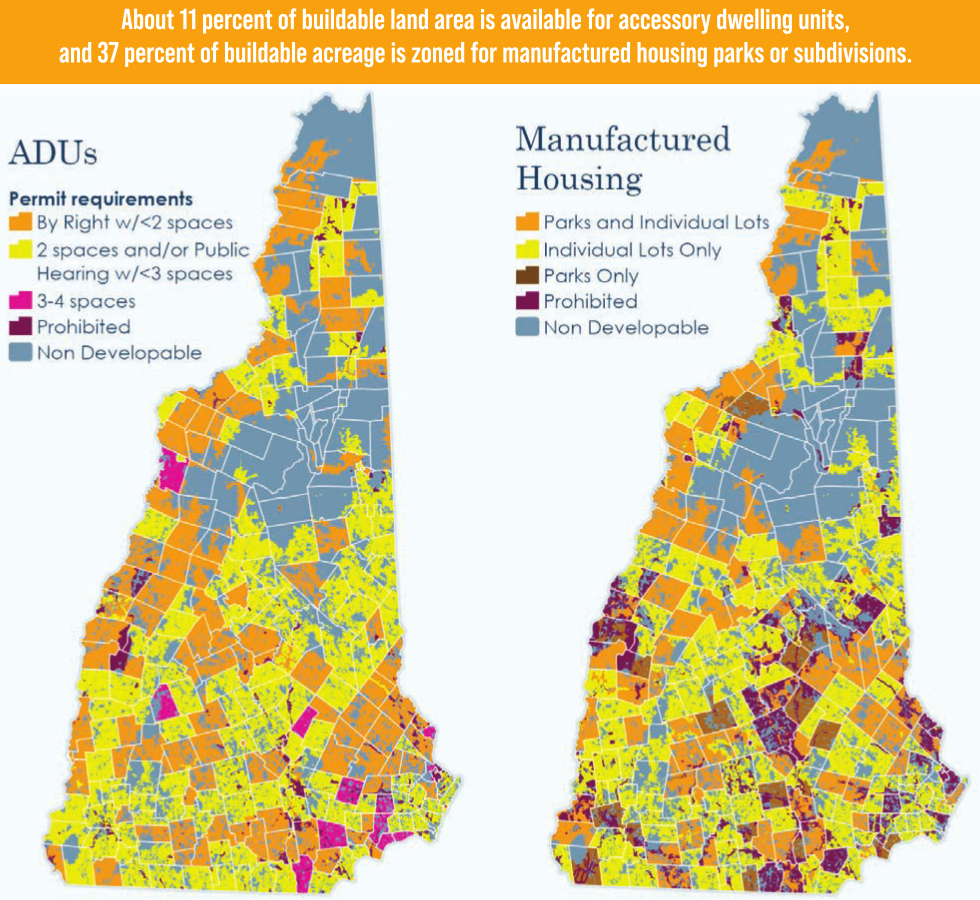

Even state law-mandated accommodations for accessory dwelling units and manufactured housing are inconsistent, according to the atlas preparers. Local regulations often make ADUs economically unfeasible, according to Sarah Marchant of the NH Community Loan Fund.

“That could be either having to go to the planning board or the zoning board for special approvals, which requires information above and beyond the building permit and usually additional expertise to be able to produce the plans and information required at those hearings,” said Marchant, another participant in Monday’s media briefing.

‘Policy-neutral’

The atlas has been more than a year in the making, the work of the Center for Ethics in Society at St. Anselm College, NH Housing and the NH Department of Business and Economic Affairs. Several underwriters helped with the $100,000 cost of the project, including the NH Realtors Association.

“I do want to emphasize that the atlas project is policy-neutral, so it does not take a position exactly on what changes New Hampshire or communities need to make or how those changes might be made,” said Max Latona, executive director of the ethics center at St. Anselm. “What we want to do is have our policymakers both at the state and local level have an informed discussion about the ways in which zoning in our communities both individually, but also collectively, is affecting housing supply and affordability.”

That is underscored by separate data from NH Housing and from the Realtors.

NH Housing, in a recently released report, said the state currently needs 23,500 housing units to meet demand right now and 60,000 units to meet the demand expected between 2020 and 2030; nearly 90,000 units are needed between 2020 and 2040.

Affordability index stats from NHAR show residential affordability at an all-time low.

A value of 100 indicates that the typical median-income family has exactly enough money to qualify for a home. Any value below 100 means that a family may struggle to qualify for a mortgage on a home in a particular area. The lower the value, the greater the struggle to afford the mortgage.

In its March report, the Realtors said the affordability index for a single-family home in New Hampshire was 70, compared to 80 in March 2022. The affordability index for a residential condominium was 87 versus 101 the previous year.

The atlas delineates zoning differences between the northern and southern parts of the state.

The White Mountains region and Upper Valley are more affordable and accessible in terms of housing development versus the southern part of the state, where the workforce need is concentrated.

“It’s the places where the demand is highest where some of the restrictions tend to be higher, at least in the suburbs, where you get two- to five-acre minimum lot sizes,” said Jason Sorens of the American Institute for Economic Research.

Empowering residents, lawmakers

The New Hampshire zoning atlas is part of a national project, and New Hampshire is the third state, behind Connecticut and Montana, to finish its work. The data is current to June 1, 2022; data will be updated as needed at least annually and perhaps twice a year.

The public rollout includes a community engagement component for the next several months, during which sponsors will seek to get information about the atlas out to individuals and policymakers. For instance, a presentation will be made to the NH Planners Association spring conference June 2 at the Common Man Inn & Spa in Plymouth.

Latona sees the atlas as empowering residents and policymakers alike.

“Any member of a community could use the data in the atlas to put forward a proposal for change in a given community. Now there’s support, there’s evidence, there’s data that can support proposals for change at the community level,” he said. “So I think this could really empower those people who would like to see some adjustments in zoning and be able to put forward well-supported proposals for that.”