State sits out on $3.6 billion Northeast clean hydrogen hub proposal

A hydrogen cell bus being tested in Alexandria, Va. (Courtesy photo) Much of the Northeast joined together earlier this month in submitting a whopping $3.62 billion proposal to the federal government in hopes of becoming a regional clean hydrogen hub. Missing from the announcement was New Hampshire.

Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maine, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and more than 100 hydrogen ecosystem partners are competing for a $1.25 billion share of $8 billion in federal funding that will establish six to 10 clean hydrogen hubs around the country as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The seven participating governors issued statements about the final proposal April 7, using phrases such as “momentous day” and “game-changing,” while highlighting potential for economic growth, industry and advancement of their respective state climate goals.

Gov. Chris Sununu wasn’t among the choir of voices. And it’s not completely clear why New Hampshire didn’t throw its hat into the ring. When pressed about it shortly after the announcement later, Sununu said, “I love the idea of hydrogen.”

He directed further inquiries to the Department of Energy as to why the Granite State hadn’t joined the regional effort, but did say, “All of the pieces definitely have to be there.”

“You’ve got to have projects, you’ve got to have the developers,” Sununu said. “The state doesn’t build hydrogen plants. … To be able to make those investments would be huge. To have more low-cost energy sources, whether they’re here in New Hampshire or in the New England region as a whole, that benefits everybody.”

New Hampshire does have a significant hydrogen project on its home turf: Utah-based Q Hydrogen is redeveloping a former paper mill in Groveton into “the world’s first power plant completely fueled by clean, affordable clear hydrogen,” the company says.

The governor’s support for hydrogen makes all the more mystifying why New Hampshire did not join its neighbors in the major competition for federal dollars.

“I find this one slightly baffling, and I think a lot of folks do,” said Sam Evans-Brown, executive director of Clean Energy New Hampshire.

Chris Ellms, deputy commissioner at the Department of Energy, said while the state has been supportive of regional attempts to secure federal money for offshore wind power, the department “has opted not to join the hydrogen consortium at this time.”

“The application was submitted by a consortium of states and business partners led by the state of New York,” Ellms said. “Before the state of New Hampshire enters into an agreement with other states, there are a variety of factors that need to be considered, such as whether or not the agreement aligns with state policy goals.”

New Hampshire is the only state in New England without a statutory requirement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or a comprehensive, up-to-date climate action plan.

While answering questions from the press in his office, Gov. Chris Sununu said he ‘loves hydrogen,’ but the state has not joined a regional effort to get federal dollars to develop clean hydrogen infrastructure. (Courtesy Hadley Barndollar/New Hampshire Bulletin)

Hydrogen hype

There’s a lot of hype around hydrogen, particularly stemming from Europe’s enthusiasm for it. It’s an attractive fuel source in terms of decarbonization goals because it doesn’t produce carbon dioxide, the main culprit behind global warming.

Not all hydrogen is created equally. It can be extracted from either fossil fuels or renewable energy, and stored, transported or burned to provide power. The most common methods to produce hydrogen fuel are thermal processes and electrolysis.

A report by Allied Market Research stated the global clean hydrogen industry is anticipated to be an $18.3 billion market by 2032.

Evans-Brown feels there’s certainly a place for hydrogen in a decarbonized world, particularly in the sectors hardest to decarbonize. But he cited an “irrational exuberance” around the idea that it can “do anything.” He takes his cues, he said, from Michael Liebreich’s clean hydrogen merit ladder: a ranking system of what hydrogen should be used for.

The federal government’s endorsement of hydrogen via the regional hubs has not come without debate.

It’s not a perfect solution, critics say. There are other ways it can cause pollution, such as leaks that release methane — a potent greenhouse gas — into the atmosphere. And when burned, for example, hydrogen produces large amounts of nitrogen oxide, an air pollutant that can damage the human respiratory system.

In regards to the latter, some worry that oil and gas companies will turn to burning hydrogen and use it as a “greenwashing” tactic, a term that refers to deceptive marketing techniques to persuade the public that a company is environmentally conscious or a particular product or practice has environmental benefits.

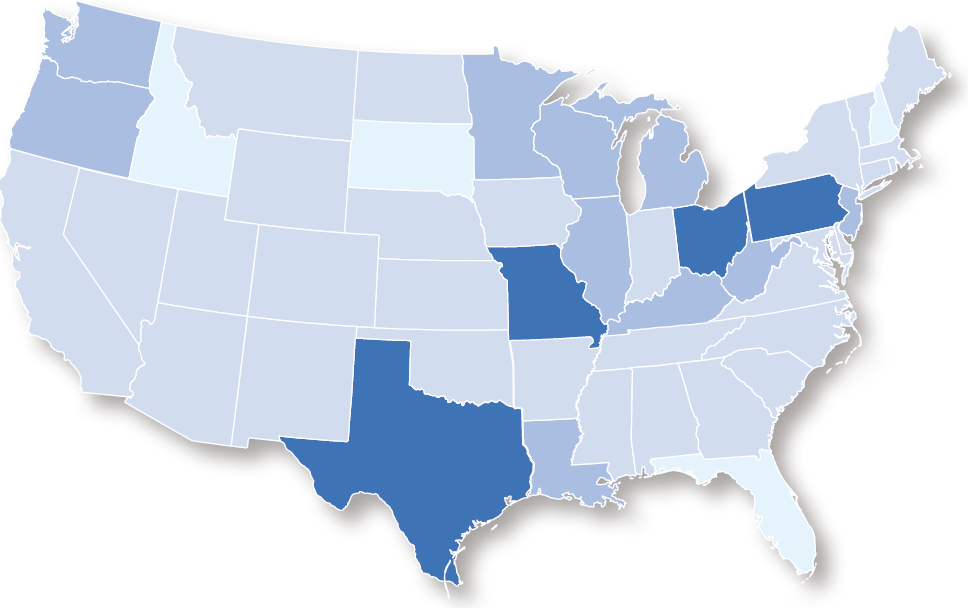

A tracking map from Clean Air Task Force shows New Hampshire is among just four states in the country that have not joined a regional clean hydrogen hub proposal. The darker the color of the state, the more proposals they’ve signed onto. (Courtesy Clean Air Task Force)

The $3.62 billion proposal

The federally funded clean hydrogen hubs will create networks of hydrogen producers, consumers and local connective infrastructure to accelerate the use of hydrogen as a clean energy carrier that can deliver or store energy, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

The New York-led consortium of Northeast states was initially announced last March. Together, the seven states are competing against other proposed hubs across the country — upwards of 20 — for a share of the federal funding.

If selected, the federal dollars would feed the Northeast’s total proposal of $3.62 billion, consisting of more than a dozen projects across all seven states “that advance clean electrolytic hydrogen production, consumption, and infrastructure projects, for hard-to-decarbonize sectors, including transportation and heavy industry, among others.”

Projects within the Northeast hub would occur within four phases of development over 10 to 12 years.

An interactive map by the Clean Air Task Force, which has been tracking the hub proposals, shows New Hampshire is one of only four states (along with Florida, South Dakota and Idaho) that have not joined at least one hub proposal.

It’s a “missed opportunity” for New Hampshire, said Evans-Brown, specifically the free federal money, “especially if another state is taking a lead on writing the application.” It’s yet another instance of New Hampshire furthering its outlier status in the region when it comes to action on climate change and clean energy.

Evans-Brown believes the state’s absence from the regional effort is indicative of its relatively new Department of Energy — created in 2021 — that doesn’t have the capacity or staff to throw its hat in the ring for competitive grants.

“Across the board, it’s like pulling teeth to get state agencies to go after this stuff,” he said.

Outside of the regional initiative, lawmakers are still trying to ready the state for the future of hydrogen.

Sen. David Watters, D-Dover, recently testified in front of the House Science, Technology, and Energy Committee on behalf of a bill he introduced to support the development of green hydrogen in the Granite State.

“I don’t want New Hampshire to be the black hole where industry says don’t go there because you can’t get anything built,” Watters said. “I want that investment to come here, both federal money and private dollars to come in, and I think we have huge potential here.”

Beatrice Burack contributed to this story. This story was originally produced by the New Hampshire Bulletin, an independent local newsroom that allows NH Business Review and other outlets to republish its reporting.