Initiatives seek to create home-grown energy sources

Green hydrogen, renewable natural gas, activated carbon: These are some of the new technologies that are being looked into in New Hampshire in an effort to save money on energy, increase self-reliance on home-grown renewable sources and to do the state’s part in the fight against climate change.

But will the technologies work, and are they economically and environmentally sound? Here’s how the technologies measure up so far in New Hampshire.

Green hydrogen

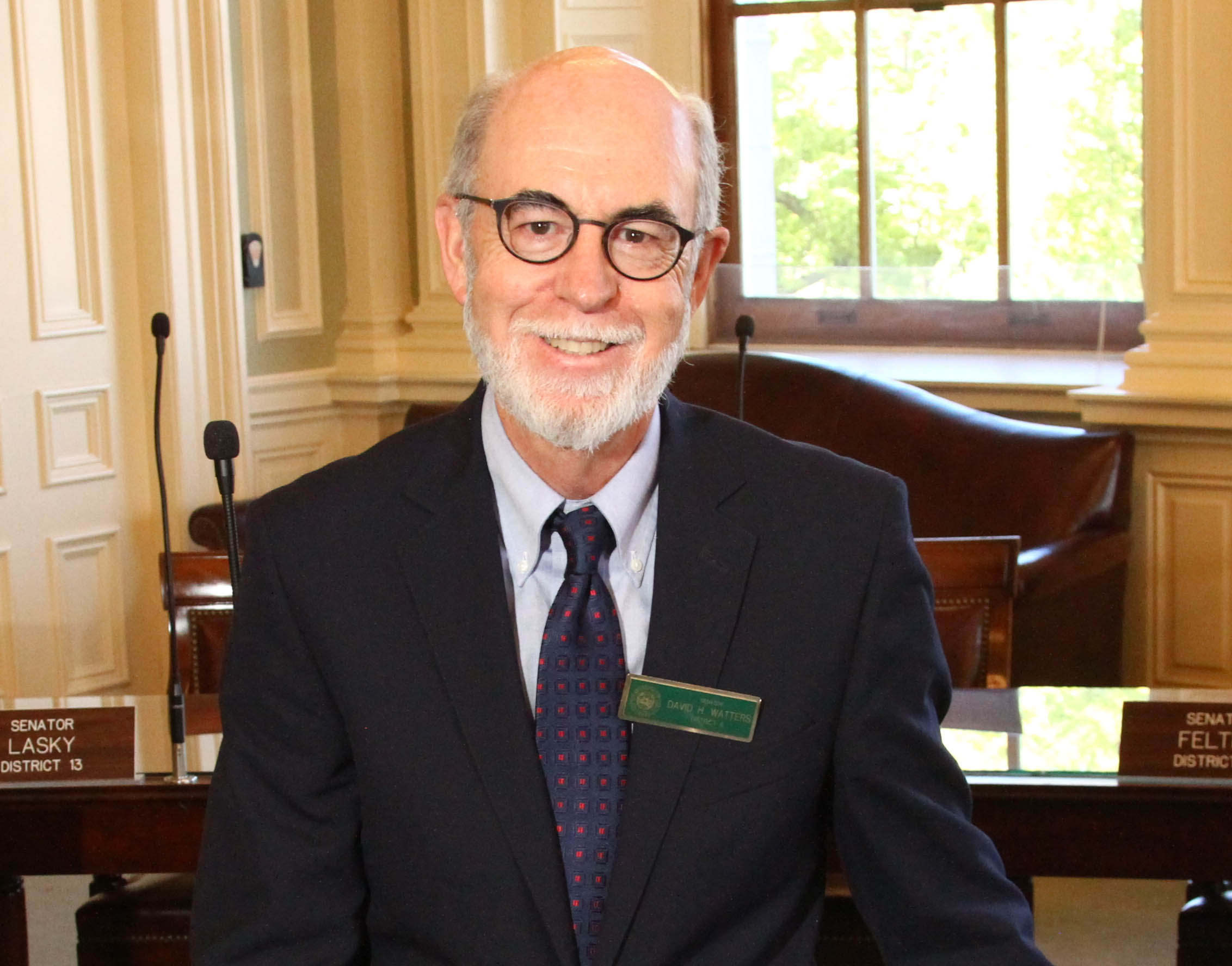

Green hydrogen — a process that involves splitting water through electrolysis to produce hydrogen — is the latest, and to hear Sen. David Watters, D-Dover, almost the greatest, renewable energy source, especially when backed with billions of federal dollars.

“Aside from offshore wind, hydrogen will be one of the most substantial changes in energy supply in the coming decades,” Watters told the Senate Energy and Natural Resource committee at a Feb. 2 hearing in introducing Senate Bill 167, which would make green hydrogen a renewable fuel and provide a business tax break to those who develop it.

Watters said the hydrogen that is produced can be used, without emitting carbon into the atmosphere for energy, as transportation fuel for marine shipping, long-haul trucking or jet fuel. It can be used for heavy manufacturing, or even to replace coal at the coal-burning Merrimack Station power plant in Bow.

‘Hydrogen will be one of the most substantial changes in energy supply in the coming decades,’ says Sen. David Watters, D-Dover, sponsor of a bill to encourage its production in the state.

James Andrews, who owns Granite Shore Power, owner of the power plant, followed Watters in endorsing his bill, though he did not say he wanted to use the fuel for his plant — the only coal-fired plant in the New England, even though Watters said he was “really interested” in that possibility.

(Andrews did not respond to NH Business Review inquiries.)

Right now, the only company seriously touting the use of hydrogen fuel, is Liberty, which is thinking eventually of employing it in Keene.

Keene is perhaps the kind of place to try out new technologies, said Neil Proudman, Liberty’s New Hampshire president. The city doesn’t get natural gas piped in from afar. Instead, it uses propane for its gas needs — the only system of its size to do so. And the system used is antiquated, Proudman told the House Science, Technology and Energy Committee in January.

“In the next few years, we have a decision to make,” he said at the time.

One possibility is to switch to renewable natural gas mixed with about 20 percent hydrogen (the most that can be blended without damaging gas appliances as well as for safety reasons, since pure hydrogen can be highly explosive).

Proudman said he had talked to Keene city officials as well as its energy committee, presenting a slide show called “Green Keene.” He noted both the utility and the city are attempting to get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

“We are excited about the project,” said Keene Mayor George Hansel, who was under the impression that it is only a few years away. “It is right in line with our stated goals.”

But the presentation was short on details. When NH Business Review pressed for them, Liberty replied via email that it was only studying the technology’s feasibility.

“Liberty presented some preliminary concepts” for converting Keene’s system, about the “art of what’s possible,” said the statement. “There’s still a lot we don’t know, but we are excited about the possibilities.”

Hydrogen as a fuel isn’t new, but green hydrogen is still pretty rare. Although colorless, hydrogen is labeled in different colors when it comes to classification, based on how it’s produced. Here’s how the Sierra Club described it in a recent report, moving from the worst environmentally (in its judgement) to the best:

Extracting it from coal is brown, making it from methane (with no CO2 capture) is gray, using methane gas with carbon capture and sequestration is blue, and using electrolysis to make it from water, is green.

Energy entrepreneur Bob Hayden has also started Blue World Power, a possible provider of activated carbon in New Hampshire.

Some 99 percent of the U.S. supply of hydrogen comes from methane, said the report, and methane has carbon in it. Currently, most of the produced hydrogen is used in diesel production, followed by production of ammonia production, chemical fertilizers and synthetic hydrocarbons for fuels and chemicals.

The report said that even green hydrogen, although it has no carbon in it, it can interact with other gases in the atmosphere that can contribute to climate change. When blended with natural gas, either to heat homes or produce power, the beneficial effect on climate change is minimal because it furthers the development natural gas, which poses a problem because of leaks of methane that contribute to climate change more than carbon gases on a per-ton basis.

The report does say that green hydrogen might be used for long-term storage and long-haul freight as well as some industrial uses.

“The question about these technologies is, how much does it cost?” said Catherine Corkery, director of the New Hampshire chapter of the Sierra Club. “If it’s being trucked, what about those emissions? What about putting that money into weatherization? This takes a lot of energy to make, and a lot of money.”

But there will be a lot of money. The last two bills passed by Congress provide massive incentives for hydrogen development.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides $9.5 billion, and the Inflation Reduction Act provides a federal tax credit and expands an existing tax credit for carbon sequestration, which is used to make blue hydrogen. The federal subsidies sidestep the whole hydrogen color scheme. Instead, it promotes ”clean” hydrogen, but the regulations defining what’s clean aren’t out yet.

Neal Proudman is president of Liberty Utilities in New Hampshire, which is working with Keene in exploring the use of ‘green hydrogen’ for its natural gas needs.

In the New Hampshire bill, Watters and some lobbyists agreed there should be some tinkering with definitions, especially to align it with federal guidelines. Watters, for instance, suggested changing the requirement that it be made with renewable energy from non-carbon sources, in order to allow it for nuclear power, as well as for allowing the blending of hydrogen.

Indeed, Watters seems to cast it as more of an economic rather than an environmental bill, arguing that the bill would show that the state is “open for business.”

When asked about environmentalist’s concern about hydrogen, he said, “Fair enough. There is some anxiety that hydrogen is a stalking horse for natural gas. However, I don’t see succeeding with offshore wind if we don’t have storage, and you can’t do heavy manufacturing with just electricity.”

Renewable natural gas

Last year, Watters was co-sponsor of another bill, SB 424, which would create a legal framework for renewable natural gas (RNG), made by transforming the methane that comes off landfills (or produced by other decomposition, such as agricultural waste, like manure). At the time, Liberty was working on a project to buy natural gas produced from methane emitted at the Bethlehem landfill owned by Casella Waste System with help of Rudarpa, a resource recovery company in Utah. The gas would be compressed into trucks and delivered to various points along the company’s pipeline system. Liberty had gone in front of the Public Utilities Commission in March 2021 with permission to sign a longterm contract for the gas.

But the bill, which was signed into law in June, actually delayed the project, because Liberty was now required to issue a request for proposal, the same way it contracts for its other energy. Citing the law, the PUC closed the docket until Liberty completed the bidding process, which it launched Nov. 4.

Submissions were returned by Dec. 5, and the utility is “reviewing those submissions and considering options,” wrote Proudman in response to a NH Business Review inquiry.

The company is asking that RNG make up about 5 percent of its annual gas supply.

Proudman added, “We don’t have to use RNG just from New Hampshire. In fact, we don’t even have to use RNG at all. The RFP is to help us to understand if this is a viable and economic option for us and our customers and the analysis and considerations will help us decide how much, if any, of that we will consider for RNG. We haven’t made that decision yet.”

John Lear, a principal at Rudarpa, said his company put in a bid, even though it already had a contract before the new law. Lear said it is currently negotiating with Liberty about price, but he seemed confident that they will work out a deal, claiming that gas produced locally will be cheaper than buying it from afar, particularly during the winter. (If Liberty doesn’t select Rudarpa, it can still move gas through Liberty’s pipeline and sell it on the open market.)

Rudarpa expects to invest a total of $37 million in the project, which he hopes to recoup in eight to 10 years, but that all depends on the final price negotiated and how much gas is finally produced.

There is some debate in the environmental community about how renewable natural gas actually is. Proponents say it’s an alternative to fracking and using the methane rather than flaring also reduces carbon emissions. But opponents say that methane will leak during transport, causing the same problems that regular natural gas causes.

Corkery, who refers to RNG as “landfill gas” or “swamp gas,” worries there will be a temptation to accelerate gas production, by “sucking it out.” The result might be more methane in the atmosphere, not less, she said.

“There is no real telling how much you are not capturing,” she said. “All of these are examples of technology that don’t really solve the problem,”

But Lear said that there would be no attempt to increase the landfill’s gas output nor could there be.

“The landfill is a living organism,” he said. “We can’t speed up production. It produces what it is capable of producing.”

Activated carbon

Bob Hayden, president of Standard Power — a consulting firm that helps municipalities buy electricity, renewable and otherwise — has also started another company, Blue World Power, as a possible provider of activated carbon.

Blue World wants to build a plant somewhere in New Hampshire to burn biomass — wood chips — without oxygen. The process, called pyrolysis, produces biochar, or activated carbon, that is almost pure carbon. The energy produced in the process could be sold to communities or nearby businesses, perhaps creating a microgrid — kind of a backup generator for important municipal buildings that must keep on going when the larger grid fails. The environmental benefit, he said, “is we are retaining the carbon. We don’t release it into the air.” There is some carbon release when it first starts up, he said, but the idea is that the plant would be constantly running.

The activated carbon product, he said, could be mixed with cow manure to produce a good fertilizer, with the carbon absorbing much of the methane that would go into the atmosphere. It can also be used as a carbon filter for water filtration systems.

Such a facility has been built in South Africa, and Hayden is bringing the person who created it to New Hampshire, hoping to build a 100,000-square-foot, 5-megawatt plant on five acres that would run 8,000 hours a year. It is currently looking at sites in Keene (where Standard Power works as the city’s community power consultant) as well as Hillsborough County, the North Country and a couple of locations in Maine. He said he has about $10 million in financing lined up.

“We’ve been working on this for a year,” he said. “It’s a startup, and like any startup, there are no guarantees, but we have a high probability of success.”