Why do certain towns have high filing rates?

On April 26, Abigail Iris Small raised her right hand and swore to tell the truth, although the bankruptcy trustee couldn’t see her do it during the creditors meeting, because her bankruptcy hearing was being held over the phone. Still, he went ahead with the usual questions.

Have you ever owned any real estate?

No.

Did you list everything you owned on the schedules?

Yes.

Small couldn’t afford an attorney, so she filled those schedules out with the help of her mother, who is a paralegal — she couldn’t afford an attorney. They showed all of her assets: a 2006 Honda, family china from Poland, an old upright piano and two parakeets, totaling $36,458.31, far short of $64,634 she owed. The schedules also showed that her annual income from her job at Lowe’s — about the same as

her assets — could not support a family of five, even with monthly

child support payments and her husband’s disability income.

The

number of bankruptcies filed in New Hampshire have plummeted since the

pandemic to all-time lows. Still, on April 26, the bankruptcy trustee

held a total of 15 hearings. Nearly every case represented a life in

disarray. And in the last four years — from the start of 2018 to the end

of 2021 — there were more than 5,200 such cases filed in the Granite

State.

NH Business

Review downloaded through the U.S. Bankruptcy Court’s PACER system every

one of those cases, and — with help from Doug Hall, a member of the

board of the NH School Funding Fairness Project — analyzed the data to

get a better idea where the people who are filing live, what they are

filing and perhaps why they are filing — especially during the pandemic

economy, when the number of bankruptcies have plunged and employment has

skyrocketed.

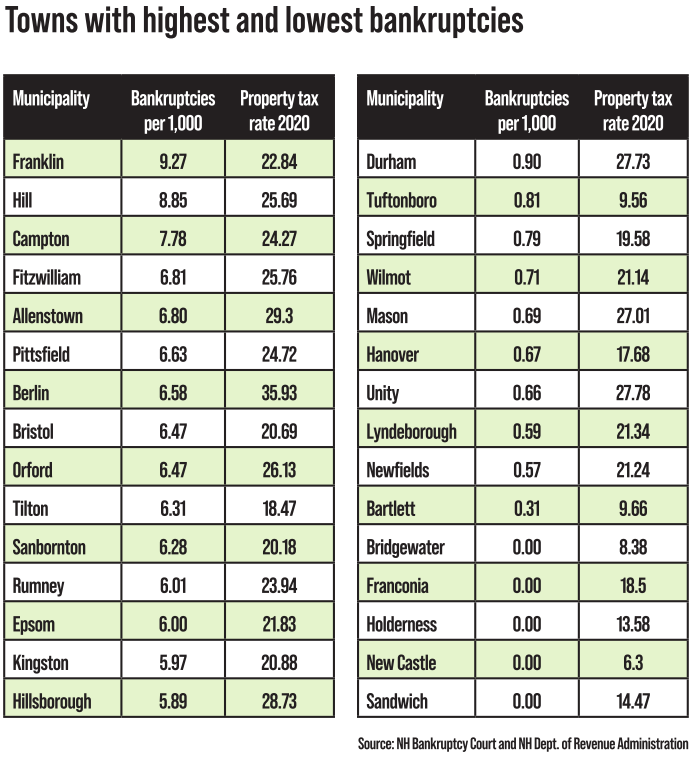

Claremont suit towns

According

to the data, communities located in the area from the Capital Region to

just north of the Lakes Region have the most bankruptcy filings per

capita. Among municipalities with more than 5,000 residents, the city of

Franklin had the most per capita filings in the state — 9.27 per

100,000 people, more than 10 times the number of Hanover, which has the

fewest, at 0.67.

The

town of Hill, right next door to Franklin, is No. 2, with 8.85 filings

per 100,000 people. Other neighboring communities — Bristol, Tilton and

Sanbornton — all have rates above 6.0. Campton, 31 miles from Franklin

in the foothills of the White Mountains, has the third highest rate,

though Holderness, about 12 miles south of Campton, had none at all.

Two other towns not far from Franklin, Allenstown and Pittsfield also had high rates of filings: 6.8 and 6.6, respectively.

Franklin, Allenstown and

Pittsfield were three of the five plaintiff towns in the landmark

Claremont schoolfunding case, which resulted in the NH Supreme Court

ruling that says the state’s property tax-based school funding system is

unconstitutional.

Other municipalities with a

large number of filings were Berlin (6.58) and Derry (5.62). In terms

of the fewest, Hanover was followed by two other college towns, Durham

and Henniker.

Hollis, which has one of the highest median household incomes in the state, had the four fewest, with 1.44 filings per 100,000.

But

poverty alone doesn’t necessarily drive bankruptcies, since the

lowest-income people have little to lose and therefore less to protect.

Bankruptcy is a way to protect assets, so it is usually filed by people

with some of them, be it a car or house. It’s also for people who are

overextended on credit, which means they are able to obtain a credit

card.

Franklin

Mayor Jo Brown isn’t quite sure why bankruptcies are so high in

Franklin. She does have a theory, though. Homes in the city are selling

like hot cakes due to outside investors buying them up cheap, and she

suspects some people are using bankruptcy to get out of debt and unload

an underwater house, though if home prices are rising, it’s unclear why

that would be necessary.

‘The great reset’

The

common perception is that job loss explains bankruptcy, since

historically the two go hand in hand, but the pandemic economy with near

record-low unemployment has poked a hole in that theory.

Bankruptcies

fell across the board during the pandemic, but at different rates.

Business-related bankruptcies fell by about 25 percent between 2019 and

2021. Consumer-related bankruptcies fell by 60 percent.

Even greater was the drop in Chapter 13 filings, which are often triggered by homeowners trying to prevent foreclosure. They

fell by 78 percent. There were hardly any foreclosures in New Hampshire

during the pandemic, thanks to government regulation that at first

halted them, along with forbearance, loan modifications and outright

subsidies to help pay the mortgage.

“It’s

the great reset,” said William Gillen, a Manchester bankruptcy

attorney, who handled the second most filings in the four-year period.

“In my humble opinion, with all these trillions flooding the market,

there was no need to file bankruptcy. There was nothing pushing people

to file. People are in debt, but the creditors were not putting them in a

headlock.”

Bankruptcy

attorneys, who were all set for a deluge following the surge of

unemployment in the spring of 2020, suddenly risked going under

themselves.

Above:

Quentin Silveria, shown on the Harley-Davidson he used to own, filed

for bankruptcy after taking a different job during Covid.

At right: River Gogh Moon of Plymouth filed for bankruptcy as the result of a car wreck in Minnesota.

“It was terrible,” Gillen said. “I’m still profitable, and I have been a pretty good squirrel putting away my acorns.”

The

courts also shut down for a while, not only slowing the bankruptcy

process, but other courts that might push people into filing for

protection. That has created a huge backlog.

“I have a civil case

pre-Covid, and it was just getting scheduled for May,” said Concord

bankruptcy attorney Sandra Kuhn, who handled the most filings.

Both

Kuhn and Gillen said that filings have been picking up as of late. In

March they rose 53 percent from February, to 65. But that is still down

from March 2021 and prepandemic levels.

Even

before the pandemic, a 2019 national study revealed that the main

reason people file is not because they were laid off but because they

couldn’t pay their medical bills or health-related issues — either the

high cost of care or time out of work. Unaffordable mortgages or

foreclosures is the second most common reason, and living beyond one’s

means, usually via credit cards, is a close third.

Providing

help to friends and relatives, student loans and divorce were also

significant reasons in about a quarter of bankruptcy filings.

Using

2021 data to avoid the economic ups and downs of 2020, there doesn’t

seem to be any relationship between employment rates in a particular

town and the number of bankruptcy filings. But there does some seem to

be a correlation between a town’s 2020 household median income, the

percentage of residents on Medicaid and property tax rates. But such

trendline statistic correlations don’t necessarily work on an individual

town-by-town basis.

More than a quarter of Franklin’s population is on Medicaid, for instance, but Berlin is even higher (28.4). Claremont

had the second-highest Medicaid percentage, and the highest property

tax rate ($40.72), though it didn’t have that high a number of

bankruptcy filings, and Franklin’s $22.84 property tax rate was more at

the center of the pack.

‘The only person working’

Individual cases are even harder to decipher than numbers.

Small,

for instance, got into financial trouble in Concord in 2018, but ended

up filing while living in Laconia four years later.

She

kept her job, even during the year and a half she was homeless after

losing her apartment in 2018. She couldn’t support a family of five on a

retail salary following her new marriage and her third child. Her

husband, who had broken his back, was disabled, she said, so “I was the

only person working.”

Her

Concord landlord asked them to leave after they fell behind on their

rent (there were also ongoing issues about upkeep, she said), and they

weren’t able to find a place to live until February 2019, when they

found one in Laconia. When her mail finally caught up to her, she

couldn’t pay off all the accumulated interest on her debt. After one

creditor took her to court, she filed for bankruptcy on April 11.

Then

there’s one of attorney Kuhn’s clients, Quentin Silveria, a 25-year-old

of Franconia who filed when he lived in Littleton. He was working,

earning $65,000 in 2020 as a manager at Staples. He went out and

splurged, buying a Harley-Davidson Street Glide and a Chevy Silverado.

He

also took a trip to Kentucky. But the crazy Covid hours got to him, he

said, so he took a pay cut and become a 9-to-5 salesman elsewhere. With

the salary cut, he had trouble keeping up with the interest rates, and

ended up owing $107,500.

He traded in his motorcycle for a 2016 Subaru Impreza, which the Bankruptcy Court let him keep, but he had to give up the Chevy.

And

River Gogh Moon, who filed as Austin Maxwell, a 24-year-old student who

now lives in Plymouth, got into trouble in Minnesota when they drove

through a stop sign covered by a branch that wrecked their brand-new Kia

Rio. They couldn’t get insurance to pay, and eventually it was

repossessed, though there is still money owed on it.

Moon

also lost their job at a shoe store in the Mall of America but was able

to collect more than $12,000 in pandemic insurance in 2020. They ended

up going back to Tilton to live with their mother and getting a job at

Lowe’s. Moon’s filing last September showed $1,846 in monthly income,

$300 less than monthly expenses, with a little more than $400 in assets

and $21,000 in liabilities.

After a summer job at the Museum at the White Mountains, Moon is now a freshman at Plymouth State majoring in museum studies.

“I’m very happy about that,” Moon said.