A century of exclusionary zoning has helped divide Manchester by income and raceAnthony Harris, left, and Shaquwan’da Allen, right, at Allen’s hair salon Rootz on Granite Street in Manchester.

A maze of invisible walls has divided Manchester since the 1920s, dictating what can be built where and, indirectly, where the city’s poorest residents can live. These walls, created by land-use zoning laws, have helped segregate the city by income and race. Experts say that even though this kind of zoning is common, it is slowing efforts to fix some of the city’s most complex issues, including the housing shortage, persistent crime hot spots, and economic and racial segregation.

Anthony Harris, 39, is one of many Manchester residents whose path to finding housing has been redirected by these walls.

Two years ago, Harris and his girlfriend, Shaquwan’da Allen, unexpectedly found themselves on the hunt for a new apartment.

“We were homeless,” he says, “and it was hard. Even though we had money, we didn’t have enough to get a place.”

After living out of their car for four or five months, Harris and Allen started saving to get their own apartment. Even though she ran her own hair salon on Granite Street, money was tight. It took a while to scrape the money together for first and last month’s rent on a two- or three-bedroom apartment. But when they thought they finally had enough, Allen started looking through the online listings.

Right away, the couple ran into problems. “So my Queen is sending me all of these apartments,” Harris says, referring to his girlfriend. Even though some of the listings looked good, scrolling down to the details made him raise the red flag. “I’m like, ‘Hey, look at the rent!’” In the areas where they preferred to live, which was anywhere outside center city, Harris says that typical prices were more than $2,000 per month for a two- or threebedroom apartment. This was far above their budget of $1,000 per month.

Even after starting the search again — this time just for one-bedrooms — they couldn’t make it work. The most affordable listing they saw was for $1,600 in some old mill buildings on the west side.

Harris and Allen looked all over: south down Jewett Street to the Mall of New Hampshire, east out Bridge Street to Eastern Avenue, and all over the west side of the river. “When I say ‘all over’ I really mean it,” he says.

But having found nothing they could afford, Allen and Harris started looking in the part of town where they preferred not to live: center city, an area that in recent years has had relatively high rates of poverty and crime, and whose neighborhoods are sometimes referred to as the tree streets. As a previously incarcerated person, Harris says he preferred not to live there, because he wanted to leave that life behind.

Everywhere the couple looked outside center city, they struck out.

“I was even telling my Queen we can stretch it to $1,250, but then we got to sacrifice something to do it,” he says. “And it just still wasn’t good enough.”

Ultimately, the couple realized they didn’t have many choices. The best deal they could find was $650 per month to split a two-bedroom apartment with a roommate in center city, so that’s where they ended up.

“We couldn’t afford to go anywhere else,” Harris says, standing in his apartment near Pulaski Park, where he often sees the homeless sleep. “It’s like we’re forced to be here and just be grateful that, you know, we do have a place when so many of us don’t.”

What Harris and Allen don’t understand, however, is why their choices were so limited in the first place, and why most of the affordable options were concentrated in center city.

With the housing crisis receiving more attention in recent years in Manchester and around the state, over the last six months the Granite State News Collaborative has looked at the history of housing policy in Manchester, New Hampshire’s largest city, to help answer that question.

Conversations with historians and housing experts, and an analysis of historical zoning data, show that the roots of today’s affordable housing shortage can be traced all the way back to the mid-1800s — to discriminatory housing policies during the reign of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, and to exclusionary land-use zoning laws since the 1930s. Zoning didn’t create the concentrations of poverty we see in the city today, but it has continued to help concentrate the city’s poor in a handful of center city neighborhoods by slowing the construction of multifamily housing elsewhere. This has kept housing and rental prices higher the farther away from City Hall you go, creating a series of invisible walls that have kept many of the city’s most disadvantaged residents from leaving the urban core.

The Manchester city government is now seeking public comments to help it rewrite its zoning laws, which will be updated at the end of the year. A better understanding of Manchester’s housing history may help planners address some of the city’s thorniest housing problems, and may help planners design more equitable solutions for the future.

Pockets of poverty and wealth

“The high rental costs have limited the housing options available to people at nearly every income level in the city,” observed an April 2021 report by Mayor Joyce Craig’s Affordable Housing Task Force. The high housing prices have hurt not just low-income residents, the report said, but also young professionals, senior citizens, families and middle-class residents — and it has only been exacerbated by the pandemic.

The statistics paint a gloomy picture for any aspiring homeowner or renter. In the decade up to 2020, median sale prices for all homes in Manchester increased by 42 percent, up from $190,000 to $271,000, according to online data from the NH Housing Finance Authority (NHHFA). In the decade up to 2021, the median rent (including utilities) for a two-bedroom apartment in Manchester increased by 58 percent, up from $976 to $1,546 per month, according to a July 2021 report by NHHFA.

The same report estimated that for the median apartment to be affordable — meaning that rent and utilities cost less than 30 percent of the occupants’ combined monthly income — the renters would need to earn nearly $62,000 per year. This is roughly $12,000 more than the typical household of renters earns in Hillsborough County, as estimated by the NHHFA report.

But stories like Harris’s highlight one aspect of the housing crisis that was not discussed in the task force’s report—even though it was mentioned in other city reports published in 2004, 2013 and 2014 — which is that would-be renters in some neighborhoods are facing even wider earnings gaps.

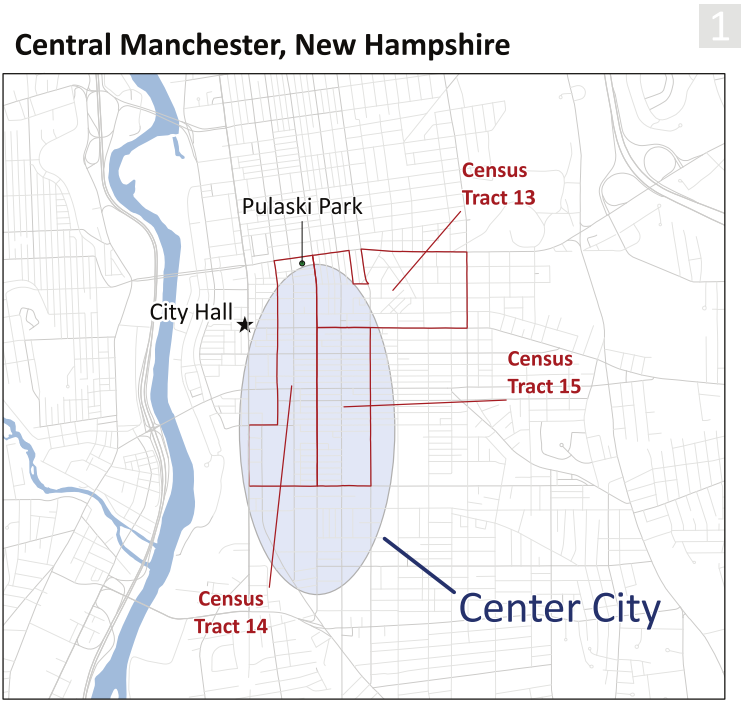

Map by the Granite State News Collaborative. Sources: IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota, www.nhgis.org; Google Maps According to 2018 U.S. Census estimates, the typical household living a few blocks east of Harris (in Census Tract 13) earned just $46,000, roughly $16,000 short of the income necessary for the typical two-bedroom apartment to be affordable. A few blocks south, the numbers are even grimmer. The typical resident living in tract 15 made just $33,000. In the neighborhood extending south from Harris’s apartment, which includes Tract 14: $23,000.

Tract 14 is home to the city’s lowest household incomes and lowest rents, on average.

But the issues in these neighborhoods go far beyond the rental market.

According to a NH Department of Health and Human Services analysis of census data, the residents of Tract 14 were the most vulnerable in the state, meaning that they were the most likely of any community to need extra help in case of a public health disaster.

Median Gross Rent is the average monthly rent agreed or contracted for plus the estimated monthly cost of utilities and fuels. Values are suppressed when the margin of error is greater than 12% of value. Data from ACS 2015-2019, Table B25064 • Source: IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota

“Overdose deaths, lifetime poverty risk and communicable disease rates are also concentrated in Manchester’s most impoverished neighborhoods,” noted a 2019 city health department report assessing the health needs of the greater Manchester area.

In the last 30 years, these inequalities have also taken on distinctive racial overtones.

Tract 14, for example, is nearly 40 percent non-white, according to the 2020 census. Right next door, Tract 15 was the only majority non-white census tract in the city or state.

By contrast, the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods are expensive to live in and overwhelmingly white. In one part of the North End, an elite enclave since the late 1800s, the poverty rate is eight times lower than in Tract 15, median incomes are three times higher, rents are 50 percent higher, and the population is 87 percent white.

This categories data is over self-reported, time. Percentages so it may calculated be influenced from by 2020 respondents' Census: changing P.L. 94-171 perceptions Redistricting of racial Data categories Summary File, over Table time. Percentages P1, and IPUMS calculated NHGIS from Table 2020 B18 Census: (time series). P.L. 94-171 Source: Redistricting IPUMS NHGIS, Data Summary University File, of Minnesota Table P1, and IPUMS NHGIS Table B18 (time series). Source: IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota

Why did these two parts of the city develop so differently? There are no easy answers to this question, nor are there easy solutions.

“I think city planning, especially for people who want diverse cities, is extraordinarily challenging,” said Elliott Berry, codirector of the Housing Justice Project at NH Legal Assistance.

“Unfortunately, sincere efforts to create diverse spaces has sometimes spurred wealthier residents to flee to suburbia,” he said. “It’s not easy for planners to find the sweet spot.”

Historians and housing experts suggest that the causes of center city’s ills are multi-faceted but can be reduced to two issues: the inequalities created by the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company’s discriminatory housing policies in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the barriers to undoing those inequalities that have been erected by local land-use zoning laws since the 1920s.

This article is being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative as part of our race and equity project. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.

For the median apartment to be affordable, renters need to earn nearly $62,000 per year.