New Hampshire’s economy, which came to a screeching halt last spring, is not only revving up this year but seems to be going full throttle on at least four cylinders.

The unemployment rate is 2.5%, and there are more jobs available than before the pandemic.

The median single-family home price, which rose 25% in May, topped $400,000, and homes are selling in an average of 25 days, at 4% more than the asking price.

Bankruptcies are at an all-time low, and when it comes to business startups, there have been 25% more new business filings year to date than before the pandemic. Business tax revenue is 29% greater than expected.

Page views on visit.nh.gov, the state’s website, are up by a quarter for the coming summer, not from last year but from 2019. Hotel occupancy is almost back to normal.

Yet, in the midst of plenty, there is scarcity. There are more than 20,000 fewer workers than there were before the pandemic. There is half as much single-home inventory. And there’s a severe shortage of supplies and materials. Exports may have increased, but imports so far have declined 17% — one of the sharpest drops in the country, reflecting severe supply chain problems.

For instance, there’s Plymouth Ski and Sports, which, among its products, sells bicycles, but won’t be able to get one until the summer of 2023, said Daniel Masera, owner for the last 26 years. Nor does he have that many who can do the selling to customers. He once had 15 people working for him but now can only get three.

During the summer of the pandemic, “there were hordes here buying anything we had.” They are still coming, but so much of his inventory is gone. It’s “like raining soup and all you have is a fork in your hand,” he said.

Finding workers

Folks are driving again, so manufacturers are making cars again. They need those rubber seals for auto doors. But Paul McDonald, general manager of Hutchinson NA, a Newfields manufacturer that makes them, couldn’t find people to work at $14.50 an hour during the pandemic, or $580 a week, when they could get $727 on enhanced unemployment. So he did the math, took a deep breath and upped the hourly pay to $17.50. That’s on top of paying about 20% more for supplies. But it has worked — he is now staffed up to 225, some 25 more employees than before the pandemic.

It is employees, in the end, that will decide the state’s economic future. For more than a year now, the government encouraged them to stay home. Now, the push is to get them back to work.

“That is our overwhelming issue,” said Brian Gottlob, director of the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau at New Hampshire Employment Security. “It all depends on how we get people working again, because there are more jobs out there than before the pandemic.”

The unemployment rate just fell from 2.8% in April to 2.5% in May, dipping below the pre-pandemic level of 2.6% in February, and early diminishing weekly unemployment claims numbers indicate there is a good chance the official rate will be even lower for June.

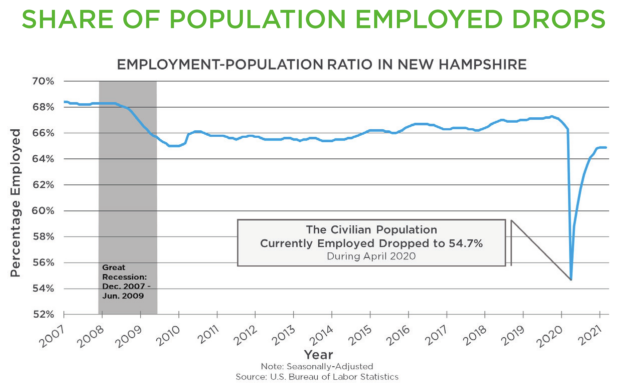

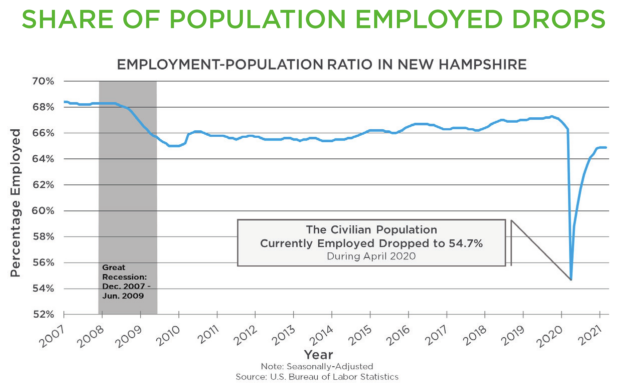

But just focusing on the unemployment rate “would be misleading,” said Gottlob, since many workers have taken themselves off the market and won’t be counted until they rejoin it.

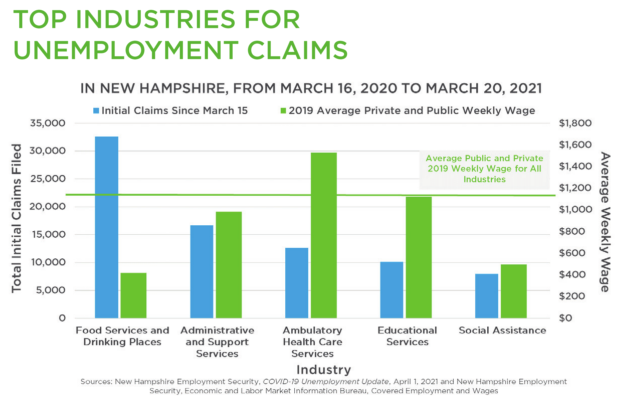

In March 2020, before the pandemic fully slammed the state’s economy, there were 24,000 more workers than there were in March 2021, with 9,000 of them in the leisure and hospitality sector, where one out of eight workers has disappeared.

A labor shortage has become a labor crisis. Alarmed, business organizations called for an early end to federal unemployment benefit enhancements that once enabled people to stay at home. Gov. Chris Sununu obliged, along with about 20 other Republican governors around the country. He brought back job search requirements in May and announced that on June 19, the state would end the $300-a-week enhancement as well as unemployment benefits for gig workers, those with Covid-related sick days and family leave, and those collecting benefits for over 26 weeks. He also offered a signing bonus — $1,000 after eight weeks for newly signed full-time workers.

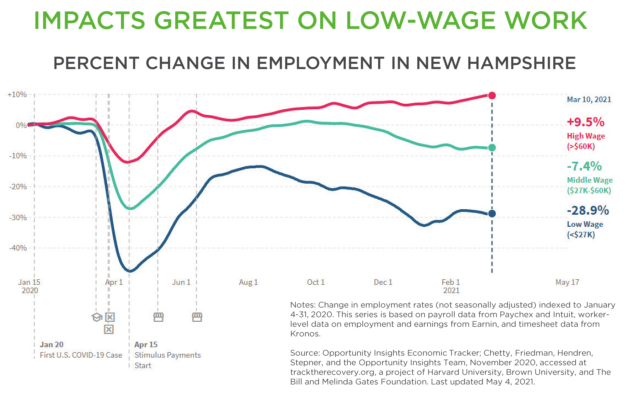

Gottlob thinks this will have an impact, especially for those on the lower end of the wage scale who saw the greatest benefit in not returning.

But not everyone agrees. “The early discontinuation of federally expanded unemployment benefits in New Hampshire may further limit” the ability of lower-wage earners “to recover and achieve economic stability, and may slow the overall economic recovery,” wrote the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute shortly after Sununu’s announcement.

Time will tell, said Gottlob. “We have a natural experiment. As a data nerd, I’m so looking forward to it.”

Inventory, inventory, inventory

When Adam Gaudet, a Concord Realtor with 603 Birch Realty, saw that the median price of a single-family home in May went over $400,000 for the first time, he said he was “stunned.”

It wasn’t the figure. After all, he sold one house for $752,000, some $92,000 over the asking price. It was the sheer price acceleration that surprised Gaudet.

The median home price — $402,000, to be exact — was $20,000 above April’s, which was $17,000 more than March. Homeowners have seen a $50,000 growth in equity since January.

There is no mystery behind the surge in prices. There is hardly any supply, combined with pent-up demand and an increase in outof-state buyers.

There were 1,517 homes for sale in the entire state in May, less than half the number of a year ago. Some 2,000 came on the market in May, but they were snapped up in an average of 25 days, exactly half the time it would have taken to sell them a year ago. And they are going for more than 4% over asking price.

While the increase in the number of out-ofstate buyers is small (from a few points under 30% to slightly over), they often come with big-city salaries and inflated stock portfolios, allowing many to pay in cash.

Nowhere have prices gone up faster than in the northern part of the state.

Homes in Coos County more than doubled in price, to $245,000, and that’s the low end of the market. In Carroll County, they went up 38.6%, to $395,000, and in Belknap County, 36.7%, to $410,000.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. All I know is that everybody wants to be here,” said Adam Dow of Dow Realty Group in Wolfeboro.

Dow recently sold a property for $6 million that sold for $4 million just two years ago. Some 200 families come to one open house in a weekend.

“Sellers are upset if it doesn’t sell on the first day,” Dow said, and buyers “are sick of having their written offers not accepted.”

Things may be slowing down, however.

Sales have increased, but only by only 6.1%. And pending sales are up only 4.4%.

“Twenty percent year over year is not sustainable,” said Bill Weidacher of KW Metropolitan in Bedford. “Wages aren’t increasing 20% year over year. We are going to see a stall in the market in late 2021.”

There aren’t that many homes for sale anyway. In Goffstown, there were five on the market. “You could look at that entire inventory in an afternoon,” Weidacher said.

But you can’t create more inventory if you can’t buy the land to put a house on it or the lumber to build it.

“Land is massively overpriced,” said Dehann Desharnais, owner of Spruce Building and Development in Candia. “And some materials are three times the price of what they were six months ago — anything in steel, and sheet-rock mud is getting hard to get. It’s crazy. The cost of material is going through the roof. At some point, something is going to give.”

You would think that loggers have been benefiting from all this, but that isn’t the way it works, said Jasen Stock, executive director of the New Hampshire Timberland Owners Association.

Sawmills are fetching a pretty penny for the lumber that they process, but they can’t get the logs. That’s because loggers are reluctant to cut because most biomass plants are shut down, resulting in the “worst low-grade market I have even seen. If they can’t sell two-thirds of everything that’s growing on a lot, is it worth it to harvest the other third?” said Stock.

Work (and shop) from home has made residential space more valuable. The opposite can be said for non-residential space. But, said Chris Norwood of commercial real estate firm The Norwood Group, “it is unfair to say office space is dead.” Although he admitted, “It is soft.”

Retail space is also not in much demand, but long leases have cushioned a depressed market, and there is some space-shifting going on. Some former retail sites are being converted to apartments, others to grocery stores.

Warehouse space, however, is another category entirely.

“It’s more about cubic feet than square feet,” said Norwood. There is plenty demand for that space, just not much supply.

A tale of two hotel markets

Ed Butler, co-owner of The Notchland Inn in Hart’s Location, stepped down from his Democratic Party leadership position in the House of Representatives to keep his business alive. Now he is having trouble keeping up with all the work.

“Advance reservations are better than they have been in five years, and I’m hearing the same from others in the area,” he said. “Things started picking up in mid-April, and the phone hasn’t stopped ringing.”

The problem is finding employees. “There are no people,” he said, saying that even with family pitching in, he is two employees short.

Tourism is back, but how much back remains to be seen, especially after a soggy start on Memorial Day weekend. But nearly 935,000 people visited the New Hampshire Division of Travel and Tourism Development website from March through June 7, compared to 438,000 last year, and 648,000 in 2019. And what they are viewing is a lot different from a year ago. Last year, it was campgrounds. The year before it was mainly day trippers, looking at the events calendar and for swimming holes. This year, it is road trips and cabins and cottages.

Website traffic doesn’t translate into actual auto traffic, of course, though that has picked up. The tourism agency, usually pretty optimistic, is being cautious in predicting near-2019 levels, which wasn’t bad — there were 3.45 million visitors that summer who spent $1.8 billion.

At the Hilton Garden Inn in Portsmouth, which just opened up its bar/lobby for the first time since the pandemic, things are returning to normal.

“Getting there,” reported general manager Troy Bergeron. “Weekends sold out, weekday at 50%.”

Statewide, weekday hotel occupancy was 53% in April 2019. Last April, when hotels were closed to all but essential workers, it plummeted to 19%, but so far this year it has bounced back to 44.2%.

But Steve Duprey, whose Concord hotels mainly handle business travel, will tell you things are still slow.

“The hotel business is the tale of two markets,” he said.

His Grappone Conference Center at the Courtyard by Marriott — which opened April 16 — is doing a quarter of the business it was doing before closing in March 2020. The hotel does capture some folks stopping on the way up north and participating in local events, with NASCAR racing coming up in July.

“We are grateful that business has picked up since last year,” Duprey said. “But we have a long way to go.”

Bob Sanders can be reached at bsanders@nhbr.com.