Proposals widen gap between poor and wealthy districts

The issue of education funding has long hovered over legislative sessions, whether it’s officially on the agenda or not. And this year is no exception.

In 2021, the question of state support for public schools has been marked by a deepening partisan rift among lawmakers. On one hand, Democrats have pressed to direct state aid to overcoming disparities in the opportunity and achievement of students that parallel disparities in the fiscal capacity among school districts. On the other, Republicans have pinched funding for public schools while seeking to use tax dollars to expand and support the role of private and parochial schools.

From

the outset, budget writers faced a $90 million shortfall in state aid

to public schools between the 2021 and 2022 fiscal years, foreshadowing

deep cuts in school budgets or steep increases in property taxes, which

would fall most heavily on cities and towns with the lowest equalized

property value per pupil.

For

instance, in Berlin, a $4.24 hike in the school tax rate would be

required to offset a loss of $2 million in state aid, adding $848 to the

tax bill of the owner of a $200,000 home. A $2.9 million decline in

state aid would require a $3.90 tax increase in Claremont. And in Troy,

at risk of losing $601,154 in state aid, a $4.60 rise in the tax rate

and $920 increase in the tax bill, would be needed.

State

aid is distributed among school districts on a perpupil basis,

beginning with a base amount of $3,787, which is supplemented by

differential aid for those students with special needs, including those

eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, which serves as a proxy for

living in or near poverty.

The deficit has three components.

First, enrollment has fallen 4% between 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic, representing $14 million.

Second,

25% fewer students are enrolled in the free and reduced-price lunch

program this year than in 2020, representing another $19 million. The

decline arose because the federal government directed all schools to

provide meals to all children whether eligible or not. So far, the

number eligible for 2021 remains to be calculated, though because of the

pandemic it is expected to be higher not lower than the year before.

Finally,

some $60 million in aid divided between fiscal capacity disparity aid,

targeted to municipalities where property values per student are

relatively low, and differential aid, targeted to municipalities where

the share of students eligible receiving free and reducedprice lunch is

relatively high, expires at the end of the current biennium.

SWEPT aside?

The

budget now being considered in the Senate adjusts the number of

students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch and trims $16.7

million from the deficit. However, it neither accounts for the drop in

enrollment due to the pandemic, which represents a decline of $14.6

million in state aid between 2020 and 2021, nor addresses the $60

million foregone with expiration of differential state aid.

The

Senate unanimously endorsed Senate Bill 13, which would compare the

enrollment in 2020 and 2021 and apply the higher number to calculate

base education aid. In 2022, state aid, less the share raised by the

statewide education property tax, or SWEPT, would amount to $605

million, an increase of $45 million that would narrow the deficit.

While

the bill funded differential aid for pupils eligible for free and

reduced-price lunch in FY 2022, the Senate, voting along party lines,

rejected an amendment to restore fiscal capacity disparity aid. But the

House Education Committee, also voting along party lines, voted to

retain SB 135 in committee, forestalling any further action until next

year’s session.

The

vote quelled consideration of two amendments offered by Rep. Dave

Luneau, a Hopkinson Democrat who chaired the Commission to Study School

Funding, which reported to the Legislature in December.

Adding

to the $45 million proposed by the Senate, his amendments would have

not only offset the deficit in state aid but also directed state aid to

the most hard-pressed school districts. Similar amendments, sponsored by

Democratic Sens. Lou D’Alessandro of Manchester and Cindy Rosenwald of

Nashua were subsequently rejected by the Senate Finance Committee.

One

amendment would provide $11.7 million in differential aid for pupils

eligible for free and reduced-price lunch not only in the 2022 fiscal

year, as the Senate proposed, but also in 2023. The second amendment

would restore and expand the fiscal capacity disparity aid, which would

distribute $48.5 million among municipalities where the equalized

property value per pupil was less than the state average of $1,201,688

in 2019.

“Let’s use state money where it’s needed most,” Luneau told the committee.

Apart

from offsetting the deficit in state aid and forestalling increases in

local property taxes, the measures proposed by the amendments would also

reduce property taxes, most significantly in municipalities with low

assessed property valuations.

Under

Luneau’s proposal, tax rates would be reduced between $1 and $4 per

$1,000 in 35 municipalities, all with equalized value per pupil below

the state average. Drawing on data compiled by the Department of Revenue

Administration, he calculated that the property tax bills on

median-priced homes would fall more than $200 in 20 municipalities, more

than $300 in another 10, more than $400 in three more, more than $500

in one and $600 in another.

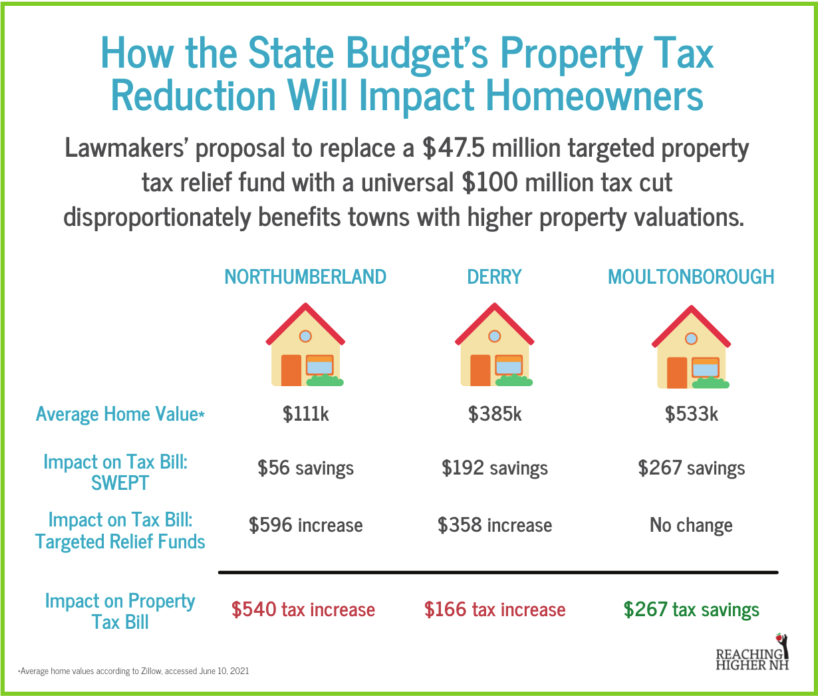

By

contrast, the House budget now before the Senate includes a reduction

in the SWEPT. Since 2005, the state has annually adjusted the rate of

the SWEPT — currently $1.825 per $1,000 of value — to raise $363

million, a fixed amount set in statute. Since the SWEPT is a state tax —

if only nominally — it is accounted for, but not deposited in, the

Education Trust Fund, a potpourri of taxes and fees from which state

education aid is drawn.

Instead, municipalities raise and retain SWEPT revenue locally and apply it

against the cost of providing an adequate education. In a number of

municipalities with high assessed property valuations, the SWEPT raises

more than enough revenue to meet the entire cost of the state’s share of

funding an adequate education and generate excess funds, which they

retain and apply to other municipal purposes.

‘Government waste’

The

proposed budget would reduce the SWEPT by $100 million in FY 2023,

which would lower the rate to about $1.30, reducing property tax rates

by an average of about 50 cents. The $100 million deficit in the

Education Trust Fund would be offset by transferring $63 million from

the general fund and drawing from a surplus in the fund itself, leaving

$83 million to be distributed among municipalities to compensate for the

reduction in SWEPT.

At the same time, the

budget provides “if any municipality’s total education grant, including

all statewide education property tax raised and retained locally, is

decreased due to the statewide education property tax reduction (the)

amounts shall be paid to impacted municipalities.”

In

other words, those municipalities foregoing excess revenue from the

SWEPT, which they retain locally, would be reimbursed by the state with

funds drawn from the Education Trust Fund, reducing the amount

distributed to school districts.

According

to one estimate, 44 cities and towns would receive reimbursements,

ranging between $563 for Dix’s Grant and $2,723,422 for Portsmouth, and

totaling $17.1 million. Five municipalities — Portsmouth,

Moultonborough, Rye, Wolfeboro and Meredith — would together receive $8

million.

“It’s all

about government waste,” Luneau insisted. “It’s about dishing out state

money where it’s not needed. A travesty against taxpayers all across the

state.”

Finally,

there is the voucher bill that would drain money in the form of the

per-pupil state grant of some $5,000, from public schools to fund

Education Freedom Accounts to provide tuition for students choosing to

leave public schools and enroll in private and parochial schools.

After

the original bill met with overwhelming opposition in the House, an

amended version (Senate Bill 130) carried the Senate on a party-line

vote and was tabled, with the expectation that it would be tacked on to

the budget rather than exposed as a standalone bill.

All

children eligible to attend public school from households with incomes

of not more than 300% of federal poverty guidelines, would qualify for

these vouchers. Reaching Higher NH, a nonpartisan education think tank,

estimates that 69,272 K-12 students, or 38% of the school population,

would be eligible, including 8,399 students already attending public and

parochial schools or being schooled at home whose education is not

currently supported by the state.

Reaching

Higher NH projects that if half the eligible privately and

home-schooled students and 2% of public school students enrolled in the

program, the cost to the state would be $21.5 million in the first year,

rising to $69.7 million by the third year.

Despite

grants to cushion against the loss of state aid due to falling

enrollment, public schools would undergo a net loss of $13.6 million.