Landlords, tenant advocates see ban as ‘ridiculous,’ ‘chaotic’

The latest moratorium aimed at preventing residential evictions, this one from the federal government, is legally dubious and comes at a time when New Hampshire evictions are at their lowest rate in six years, yet landlords who defy it could end up paying a $100,000 fine and go to jail.

Tenants could also go to jail if they lie and say they can’t pay the rent when they can, or say they are making their best effort when they are not, but there is no mechanism in place for that to happen.

The order, issued by the Centers for Disease Control, is confusing to both landlords and tenant advocates, who aren’t sure how it will be enforced. And the very uncertainty — and the severe penalties — could prevent tenants from using it and landlords from testing it.

“It’s ridiculous. It is unenforceable. But it is going to change the way we do things. I don’t see an economical way to challenge it,” said Brian C. Shaughnessy, a Bedford attorney who represents landlords and tenants.

“It’s definitely needed,” said Eliot Berry, co-director of the Housing Justice Project at New Hampshire Legal Assistance.

“But it is somewhat chaotic.”

The emergency order, pushed by the CDC at the bidding of President Trump, was put into place Sept. 4 and expires Jan. 1.

It makes it a federal crime for a landlord to evict a tenant if the tenant presents a declaration attesting, under penalty of perjury, the following:

• I am unable to pay my full rent or make a full housing payment due to substantial loss of household income … or extraordinary out-of-pocket medical expenses.

• I am using best efforts to make timely partial payments that are as close to the full payment as the individual’s circumstances may permit.

• If evicted I would likely become homeless, or need to move into a new residence shared by other people who live in close quarters.

• I understand that I must still pay rent.

• I further understand that at the end of this temporary halt on evictions on Dec. 31, 2020, my housing provider may require payment in full.

Confusing for the courts

The new moratorium, like state and federal orders before it, allows evictions for other actions besides non-payment of rent, such as engaging in criminal activity on the premises, threatening other tenants, damaging property, violating safety and health regulations and otherwise violating the lease. (A landlord can’t evict just because a lease expires, since the term lease automatically becomes a month-tomonth lease affording the tenant the same protections under New Hampshire case law.)

If a landlord receives this declaration (from each signer of the lease), he must not start an eviction, or if one is in the process, notify the court and halt it.

There is no requirement that the tenant document whether any of what is written is true, nor at present is there any way for a landlord to contest it. Some aspects are so vague — “best efforts … as the individual circumstances permit,” for instance —that it would hard to prove in the negative in any case.

Berry said he isn’t sure if a landlord could challenge the document in housing court, but Shaughnessy said he wouldn’t advise a client to risk it, since there might be a huge fine imposed for proceeding after getting the document.

The moratorium’s rules are so confusing even the court isn’t sure about them.

“Absent further guidance from the CDC or other federal authorities, it is not clear whether a state court may review the truthfulness of a tenant’s declaration. Given the uncertainty, landlords and tenants are advised to seek legal counsel about the appropriate venue, if any, for litigating the validity of a declaration,” said one circuit judge in response to a NH Business Review inquiry.

One unlikely route is to file a civil suit in state court for money damages. By using the tools of discovery, the landlord could show that the tenant did have the money to pay, but the legal costs are not worth the monetary damages — if they could ever be collected. As for perjury, that’s a criminal matter, and it would be up to the discretion of the attorney general or a county attorney to pursue, if the landlord decides to press charges.

All of these are long processes, likely to last beyond Jan. 1, “and by then it’s all over,” Shaughnessy said If it is challenged, he said, it is likely to be not for the money but over the principal, a test case.

In fact, when it comes to a test case, Shaughnessy said he thinks an organization might have a good shot to “blow this out of the water.”

Federal law usually preempts state law, but that’s when regulating the same activity. Federal law regulates federally subsidized housing, either property with federal mortgages or buildings with Section 8 tenants. But this federal moratorium effects all housing, federally backed and otherwise, and that is normally only regulated by the state.

The New Hampshire Legislature passed its own sixmonth moratorium that would have required a landlord to provide and the tenant adhere to a specific payment plan, which in retrospect seems preferable to the CDC order, Shaughnessy said.

But that bill — shepherded by Senate Majority Leader Sen. Dan Feltes, the current Democratic candidate for governor — was vetoed by the Republican incumbent, Gov. Chris Sununu.

The CDC order, which isn’t even a law, shouldn’t be able to override state housing law, Shaughnessy said. It might if it is an s emergency, which the order contends it is, but Shaughnessy thinks that could be challenged.

“I don’t think we have a fresh threshold. This pandemic has been going on for months and months, and no big deal when it comes to housing. But now, when there is election looming, it’s all of a sudden an emergency.”

‘A terrible blow to landlords’

All of this is theoretically moot if a landlord doesn’t receive a tenant declaration under the CDC moratorium.

A state Supreme Court order, issued Sept. 8, requires landlords to sign a document saying whether they have received one if an eviction is to proceed, and so for landlords have filed 50. If no declaration is received, a landlord is legally free to evict as if the moratorium doesn’t exist.

But it does. The moratorium doesn’t require a landlord to notify the tenant of the need for an affidavit, nor does it require the court to do so. Shaughnessy advises against doing so — even for landlords tempted to bend over backward to help the tenant they are trying to evict — since that amounts to giving legal advice to the tenant that might result in perjury charges.

Knowing this, many landlords may not even start a proceeding, knowing that the tenant can halt the proceedings at any time with the declaration. Most will likely just wait until Jan. 1, when the order expires, un less of course it is renewed. At that point, a landlord can demand all back rent, including late fees and interest.

Such a possibility worries Berry, who noted that January is an even worse time to get evicted than September. He urged tenants to keep current on rent as much as possible.

Landlords are more than concerned. They are angry. “It’s a terrible blow to landlords,” said Dick Anagnost, president of Anagnost Investments Inc., a large residential and commercial real estate firm. “I have tenants that haven’t paid rent since April.”

The CDC “is asking landlords to become welfare agency of the state,” said Nick Norman, legislative affairs director of the Apartment Association of New Hampshire. “It doesn’t say all grocery stores have to give away food. Why should it say that landlords have to provide housing for free?” Norman also argued that the moratorium is not needed.

“No landlord wants to evict a tenant. It doesn’t make any business sense to have to find another person.”

Evictions, he said, are only needed for a minority who are trying to “game the system.”

Anagnost estimates that 10% of a couple of thousand of residential tenants in his buildings are behind, and all but eight seem to be making payments in good faith under payment plans. And both he and Norman said they or anyone they know had yet to receive a single declaration during the first week.

No eviction tsunami

So far, statewide statistics seem to confirm the current lack of urgency.

The moratorium is designed to prevent a tsunami of evictions once the aid runs out. But the aid has been running out, and the expected deluge of evictions has yet to materialize.

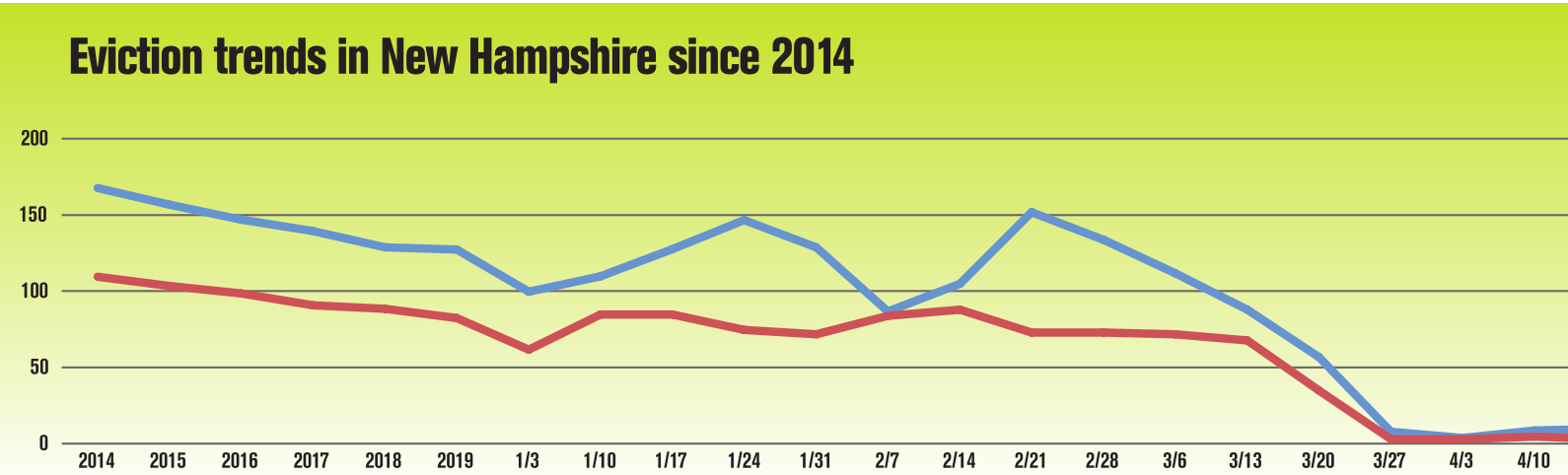

According to District Court records, the number of evictions — or writs of possession, which can sometimes be resolved before an actual eviction — has been going down since 2014, from an average of 107 a week to 80 a week in 2019, and the first months before the pandemic.

Then in mid-March, the pandemic struck and Sununu issued an eviction ban that expired in July. Weekly evictions sunk to the single digits. They jumped up, presumably because of pent-up demand, peaking in mid-July at 105, less than the average in 2014. The average number of evictions between the two moratoria was 67 a week, down by 16% than before the pandemic.

A time lag could explain the lack of an eviction surge. It simply takes time to obtain a writ of possession, though the initial filings for one also decreased from an average of 114 before the pandemic to 108 between the moratoria.

The other explanation might be all the federal help that was provided through the enhanced unemployment benefits of $600 a week, which on average replaced and sometimes exceeded what workers were making before the pandemic.

That enhancement expired in July, but it was replaced by a $300 enhancement through another executive order, this one by President Trump though the Federal Emergency Management Agency. But that enhancement will end when FEMA’s coffers grow low, which is expected to happen any week now.

Congress might extend or enhance the $300, but at deadline most observers think that won’t happen before the election.

Congress is also talking about direct rental assistance.

But the state already offers that, and most hasn’t even been used.

In mid-June, Sununu allocated $35 million through the CARES Act to help tenants via one-time grants of up to $2,500. At the time, some tenant advocates worried whether that might be enough.

The funds — distributed through the state’s five Community Action Program organizations — was slow to get off the ground, but in the last few weeks, the application process has been streamlined.

Still, there doesn’t seem to have been a run on the program. In its first seven weeks, ending Sept. 3, the program had spent $2.2 million to help 889 tenants, less than 10% of the allocation.

That pace could pick up, said Lisa English, assistant director of policy and intergovernmental affairs at the Governor’s Office of Emergency Relief and Recovery, or GO-FERR, the agency that oversees the CARES Act funds.

“We don’t know what will happen over time, but we want to make sure that anyone who needs these funds, please apply. That’s what they are there for,” she said.

But GOFERR asking for applications, rather than being overwhelmed by them, shows that the need so far has not been as great as expectations. Unless that need greatly increases, it is difficult to imagine that all of that $35 million — or even half of it — will be spent before year’s end. And, according to the CARES Act, the state has to return all the money it doesn’t spend on Jan. 1 — the same day the CDC moratorium ends.

The new year also brings other changes. The federal expansion of eligibility for unemployment will end for business owners, independent contractors and those staying home to care for themselves and family due to Covid-19. A lot of people’s basic unemployment benefits will run out as well. And those who received Trump’s payroll tax deferment will have to pay it back. Will the economy improve enough by then, or will it succumb to a second wave of the pandemic? Will that wave finally turn into that feared tsunami of evictions, foreclosures and bankruptcies?

But there will also be a new federal Congress and state legislature in January, as well as — possibly — a new president and governor, perhaps meaning action will be taken that hadn’t been before.

In this context, the phrase, “Wait ‘til next year” has both a hopeful and an ominous ring to it.