Pandemic and recession have exacerbated existing trends

“Who would have thought we’d have rising house prices despite 15% unemployment and eroding state and national economies?” asked economist Russ Thibeault of Laconiabased Applied Economic Research, who has followed New Hampshire real estate for decades.

What Thibeault called “a convoluted market,” in which homes are selling at a quicker pace and higher prices but in lower volume than a year ago — when the coronavirus was unknown and the economy was thriving — is much less the result of the pandemic and recession than of trends in the housing sector stretching back years.

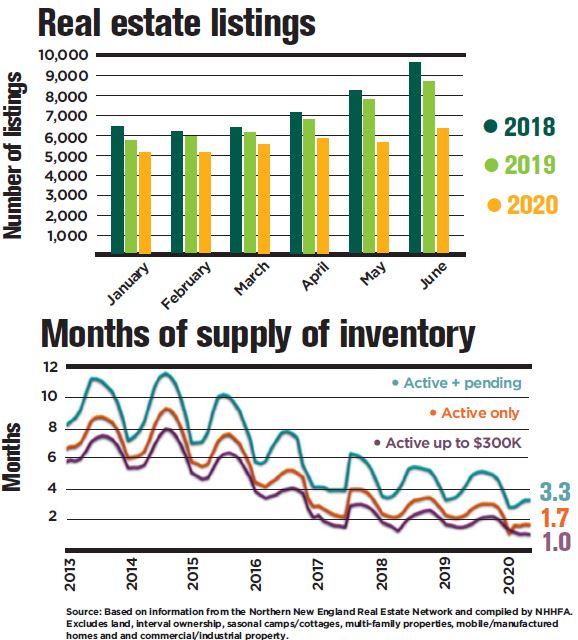

When the virus struck and the economy slumped, housing inventory, which had already been shrinking for years, reached its lowest point since before the turn of the century. Both listings and building permits fell sharply with the Great Recession and have lingered below half their peak levels since.

When the year began, data compiled by the New Hampshire Association of Realtors indicated that without new listings, the stock of single-family homes would be exhausted in less than two months and condominiums slightly sooner. Although listings have increased since then, in May the number of single-family homes and condominiums for sale were 40% and 22 fewer than in the same month a year ago, which was 17% less than a year earlier and 20% less than the year before that.

As supply tightened, prices rose. The New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority reported in March that listings have fallen 41% since 2015, with listings for properties priced below $300,000 dropping 58% while those above $300,000 have fallen just 8%.

Likewise, during the past five years sales of homes priced below $100,000 and $149,000 have decreased by 58%. At the same time, sales of homes priced between $200,000 and $299,000 have increased by 33%, between $300,000 and $399,000 by 116%, between $400,000 and $499,000 by 149% and sales priced above $500,000 by 130%.

Early in April, the NH Union Leader reported that home sales stalled as both sellers and buyers withdrew amid the economic disruption and rising unemployment wrought by the viral outbreak, suggesting that the slump “could push home prices lower.” A month later, the Concord Monitor declared “the business of buying, selling and refinancing residences hasn’t slowed at all” and WMUR-TV described the market as “sizzling hot.”

In fact, despite the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, emergency orders, high employment and shaken financial markets, year-over-year March sales totaled 1,068, down just 1.2%, and pending sales were flat while properties spent fewer days on the market and fetched prices 9% higher.

And inventories continued to shrink — single-family homes by 25% and condominiums by 13%.

According to year-over-year data compiled by the New Hampshire Association of Realtors, these indicators don’t only reflect the first quarter of 2020. Since 2017, year-over-year statistics indicate that sales have increased less than 1% ,while the median price of sales has risen and both the number of days on the market and the measures of inventory — months of supply, new listings and homes for sale — have diminished.

This pattern — fewer but faster sales at rising prices amid dwindling inventory — hardened in April and May, even as sellers became more willing to list homes and buyers were attracted by unusually low interest rates. Sales climbed to 1,449 in April, then slipped to 1,234 in May, representing year-over-year declines of 14% and 25%. But median prices continued to rise — by 13% in April and 7% in May — and time on the market continued to shorten.

Through May, year-over-year sales of single-family homes declined in all ten counties while median sale prices increased and properties sold faster in eight.

Even more volatile

As Dave Cummings, director of communications at the NHAR put it, “Inventory is historically low, and there are far more buyers than sellers. It’s not about the volume of sales but the rate of sales. If you have the listings, you’re doing well.”

“The inventory problem has been exacerbated by the virus,” Cummings said.

“What was volatile has become more so.” He anticipated that the pent-up demand and higher prices will prompt sellers to reenter the market once the uncertainty sparked by the virus passes while low interest rates will continue to draw buyers.

In June 2019, the median sales price of a single-family home in New Hampshire reached a new peak of $300,00, which was surpassed last month when the figure touched $319,900.

The increase in median sales price has far outpaced the growth of median household income. The NHFFA notes that years ago the price-to-income guideline for buyers was a property costing twice their gross household income. At the current historically high prices, buyers need three times their income to purchase a home.

Increased listings alone are unlikely to redress the imbalance of supply and demand that has come to characterize the housing market, putting upward pressure on prices. The NHHFA estimates that as many as 20,000 to 30,000 housing units are required “to meet the demand of our state’s workforce and continue our economic growth.”

Several bills, all designed to facilitate and encourage the construction of housing, especially so-called workforce housing within the means of low and moderate income households, never came to a vote with this year’s sessions of the Legislature disrupted by the coronavirus and hamstrung by partisanship.